by Nootan Bharani, AIA, Lead Design Manager

On October 8th, the Glessner House Museum, in partnership with Landmarks Illinois, the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and Friends of Historic Second Presbyterian Church, hosted a day-long symposium on historic preservation. As promoted by the hosts:

This day-long symposium event will celebrate one of the first great preservation success stories in Chicago, explore why we continue to save old buildings in the 21st century, and generate broad input into the future of historic preservation, its role in society now and for generations to come.

Nootan was invited to participate in the symposium's panel, The Future of the Historic Preservation Movement.

“Early building preservation movements were acts of activism.”

The 50th anniversary of the enactment of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) was at the heart of the day-long symposium. The day's activities included a case study presentation on the Glessner House, a review of NHPA's impact since its enactment, and a keynote by writer and human rights activist Jamie Kalven. The day closed with a guest panel, The Future of the Historic Preservation Movement. The event sought to look backward and forward at the legacy and development of this niche profession.

I admit that throughout the morning, I had moments of intense Imposter Syndrome. I doubted the value of my presence and input at the impending panel, and kept wondering: Why was I invited here? How can my experience, mainly in adaptive re-use, possibly influence a generation of folks that have done exceptional work in technical building preservation? I worried there would be retribution from traditional preservationists, if they learned about how I had to make hard choices to alter details in old buildings.

“New ideas must use old buildings.”

As discussions continued during the day, I learned that the origins of the Historic Preservation movement actually have a lot in common with the work that I do. I discovered that early building preservation movements were acts of activism—where communities found common ground in the collective effort to save structures endangered by outside interests entering the neighborhood. Preservation became a vehicle for communities to find agency in saving important cultural icons in their communities.

An example would be the preservation efforts that occurred during the 60s in Lower Manhattan. These efforts united culturally disparate communities in pursuit of a shared goal: to protect their places. This movement to preserve and protect their buildings from the impositions of outside forces is credited in part for keeping the community united.

Though not expressed in the discussions, I felt that early preservation movements, of which there are many examples all across the country, shared a commonality: the story of the local communities at the time of the preservation efforts are just as significant as the stories of the earlier communities who created the structures. To include and amplify both narratives in the preservation process cultivates community pride in the building.

“...the story of the local communities at the time of the preservation efforts are just as significant as the stories of the earlier communities who created the structures. ”

It was this thought that made me realize why I was invited to speak at the panel. Layered storytelling about a singular place was a concept I was already intending to discuss in my presentation. Somewhere along the way in legitimizing and formalizing the Historic Preservation process, an important reason to preserve at all had become lost: the creation and nurturing of community pride in place.

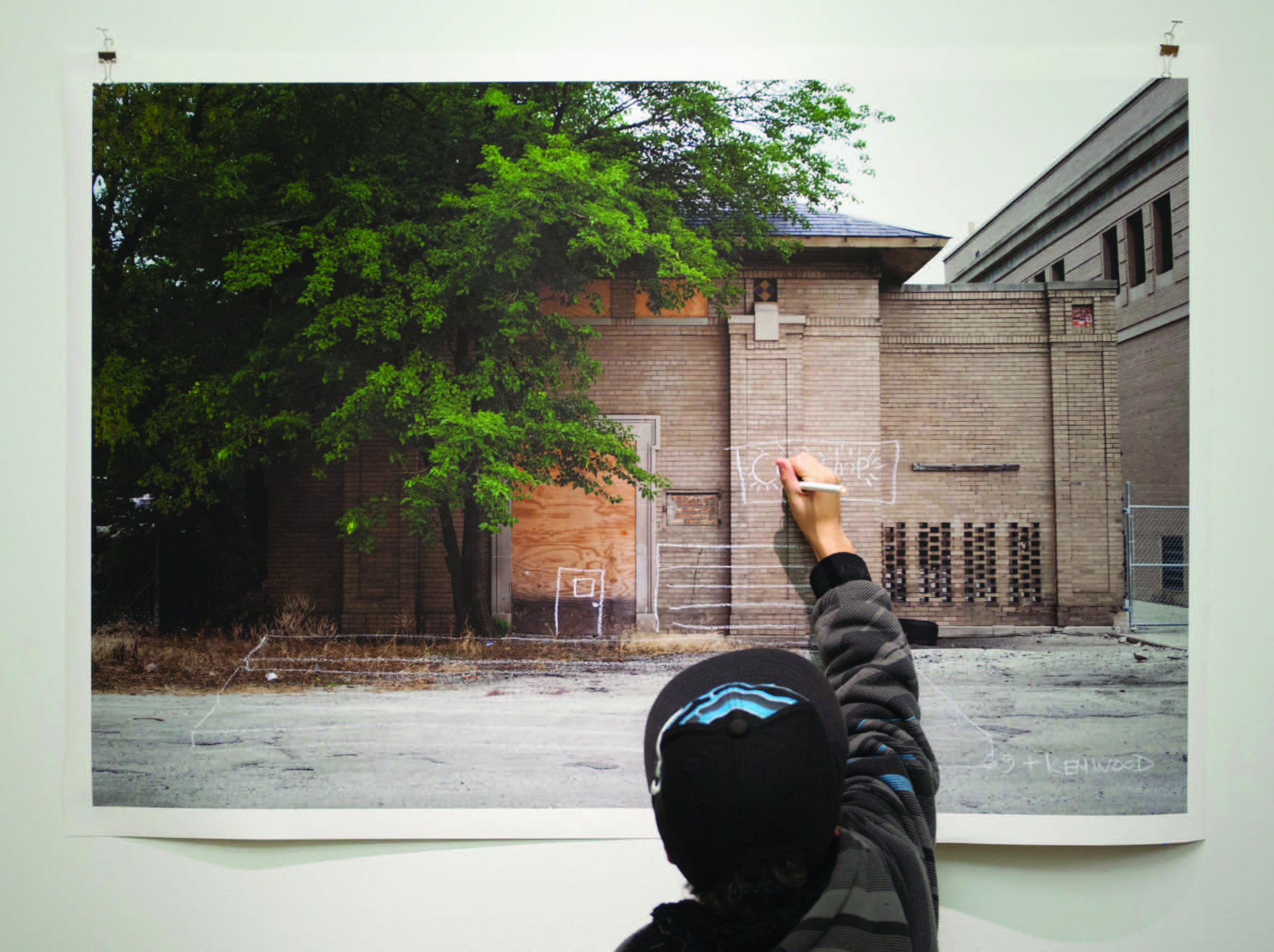

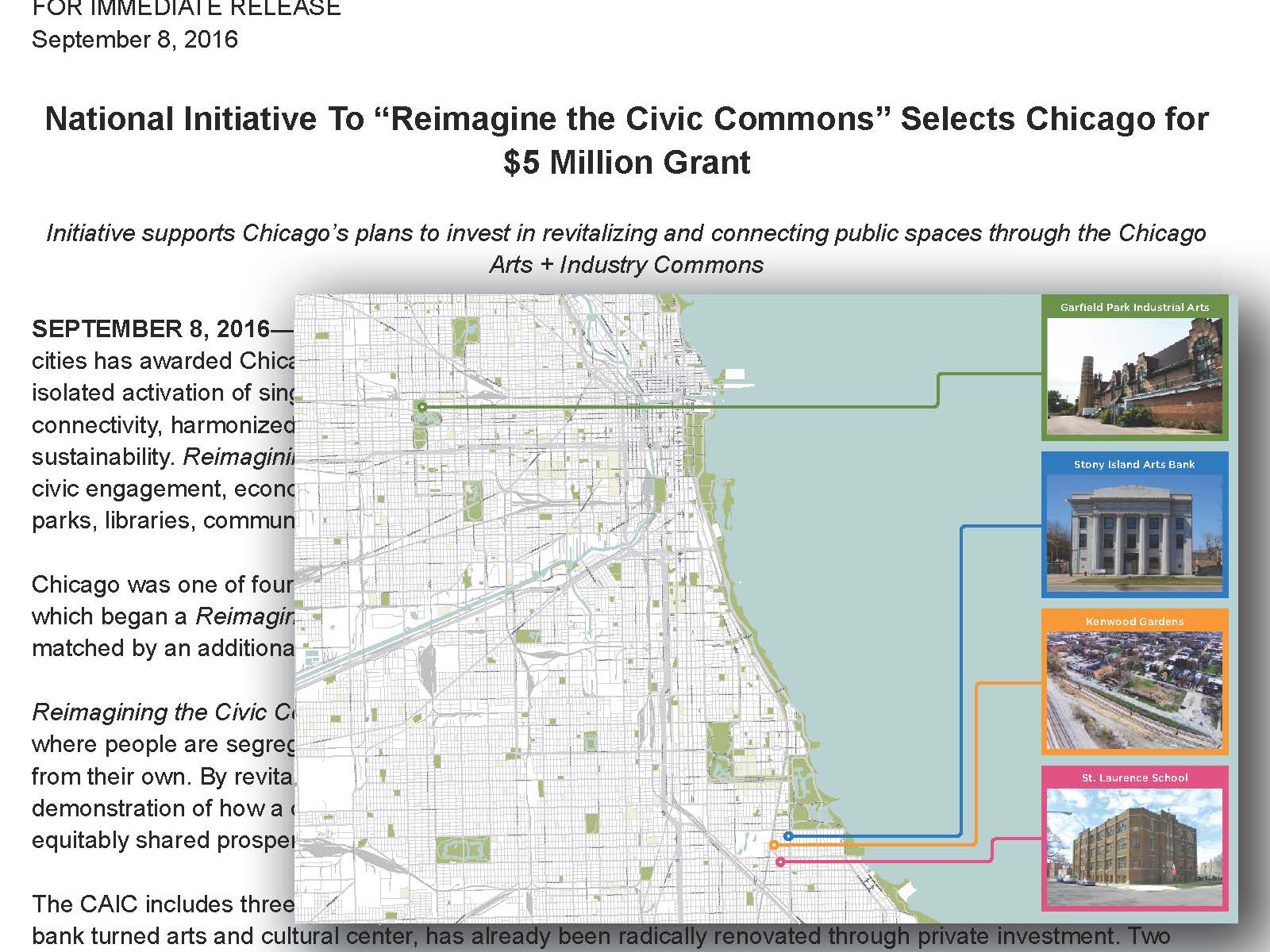

Place Lab works with all of the entities that have been created by artist Theaster Gates to bring the contemporary community’s relationship with the built environment to the forefront, while also honoring past communities.

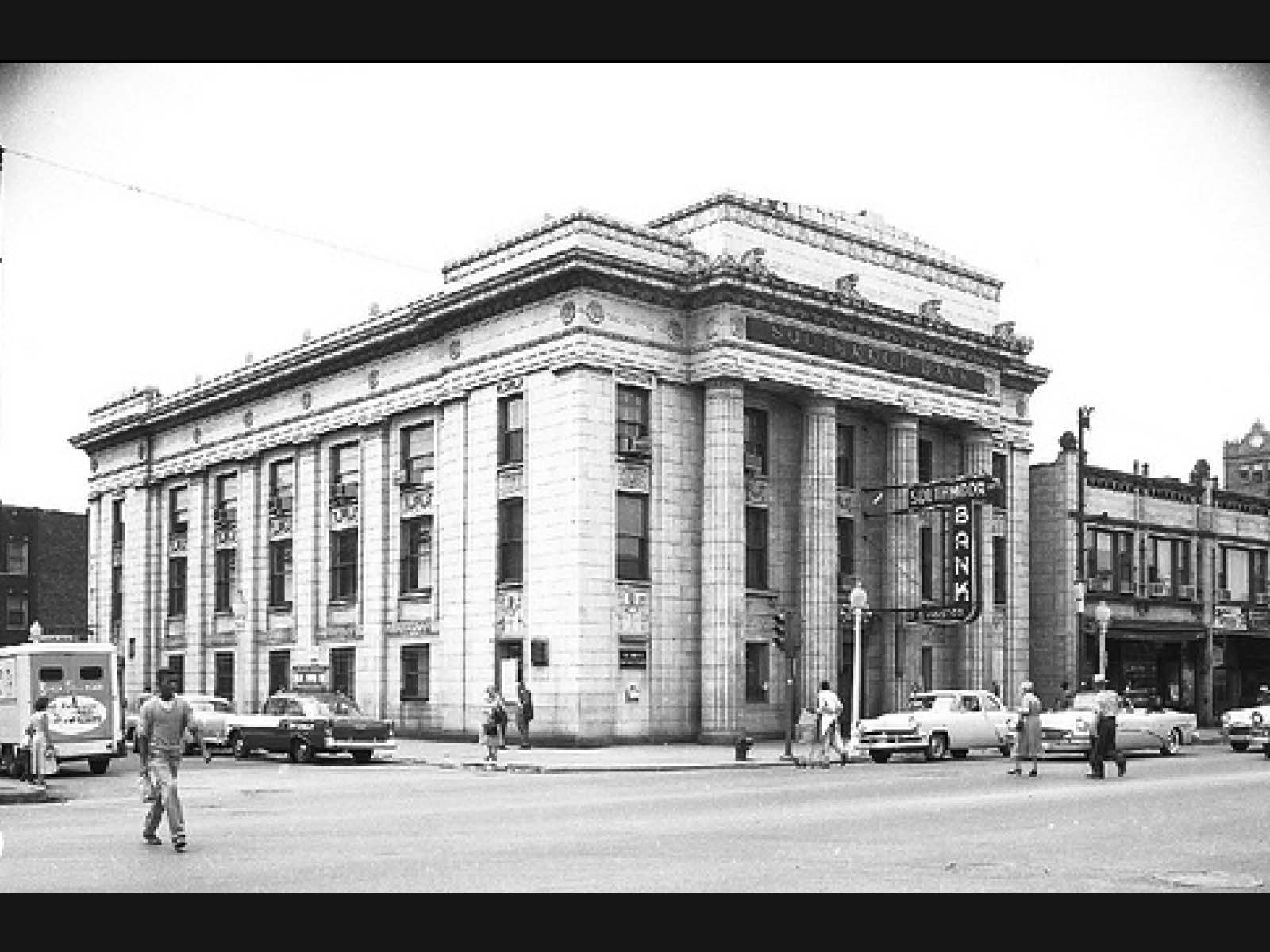

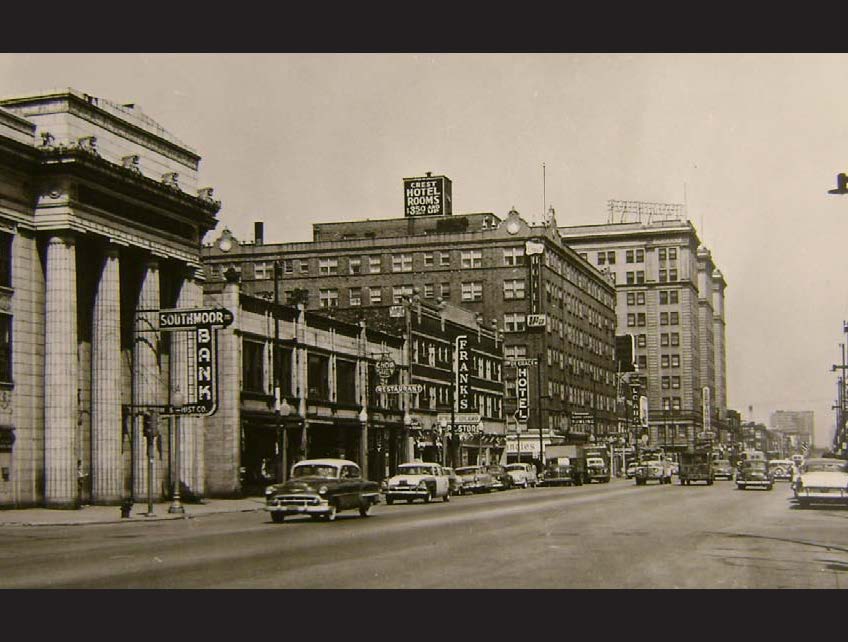

The adaptive re-use of the Stony Island Arts Bank exemplifies this approach. Designed by William Gibbons Uffendell and built in 1923, the bank has a storied history. In the 60s and 70s, the Bank was where the grandparents of today's generation secured loans to launch businesses or purchase homes; where great uncles and aunts saved for their families’ futures. At one point, the savings and loan was black-owned; it provided access to credit to a historically excluded people, and served as an emblem of autonomy and self-determination in the neighborhood. The preservation of this community anchor aimed to recall this heritage while simultaneously preparing the bank for its next life.

The same reverence for the meaning of place was at the heart of early preservationists’ efforts, but that value seems to have been eroded over time. Historic preservation's original aim was to prioritize communities over buildings—a good thing—and highlight the stories of people alongside the stories of place. That there is a multiplicity of narratives isn't considered in the current formal process of preservation. Our approach at Place Lab is to layer multiple stories—of the past, the present, and the possible future—to develop an even greater narrative of pride in place.

A return to the belief that the narrative of people and place are strongly interdependent may mark the direction for the Future of Preservation.