Photo by Phil Brown

Ethical Redevelopment Salon Series

By Aaron Rose

“There are, it seems, two muses: the Muse of Inspiration, who gives us inarticulate visions and desires, and the Muse of Realization, who returns again and again to say ‘It is yet more difficult than you thought.’ This is the muse of form. It may be then that form serves us best when it works as an obstruction, to baffle us and deflect our intended course. It may be that when we no longer know what to do, we have come to our real work and when we no longer know which way to go, we have begun our real journey. The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.”

This quote from writer, activist, and cultural critic Wendell Berry came across my screen in late spring, as the Ethical Redevelopment Salon series was coming to completion. It reminded me of an early watchword from Theaster Gates. Addressing Principle #1, Repurpose + Re-propose, he said “[a]s soon as you propose that the thing you have will become something else, the challenges begin.”

Transitions

The year-long Salon series coincided with the arc of transition in national leadership, an unprecedented crisis fueling a renewed urgency to address injustices simmering since the great social upheavals of the mid-20th century. As forces of resistance deepen their entrenchment, it’s time to invoke the kind of power that people who would block progress do not possess: compassion, trust, and vision of the possible.

There Are No Rules or How We Get This Done

We learn all the rules—and then we make our own new rules. When we work for change, if we are funded by institutions that are sanctioned channels for change, we craft goals and devise metrics that often, as was pointed out frequently during Salons Sessions, transform the change-making process into something that feels, if not looks, like what it was intended to change.

But as each obstacle, each new source of frustration presents itself, we make adjustments on the path, refine our strategy, until that breakthrough moment presents itself—when the lesson adds to the understanding, expands the toolkit, and creates the stepping stone we need to meet the next challenge and opportunity in a way that promises a project will be more inclusive and more sustainable.

What does it mean for us to invent structures that initially are just like baby leaves, and turn into branches, and turn into strong timbers? …[S]tructures don’t just land, they take hard work and a kind of slow growth to create the kind of necessary infrastructure whereby a place might change from the inside. That takes time.

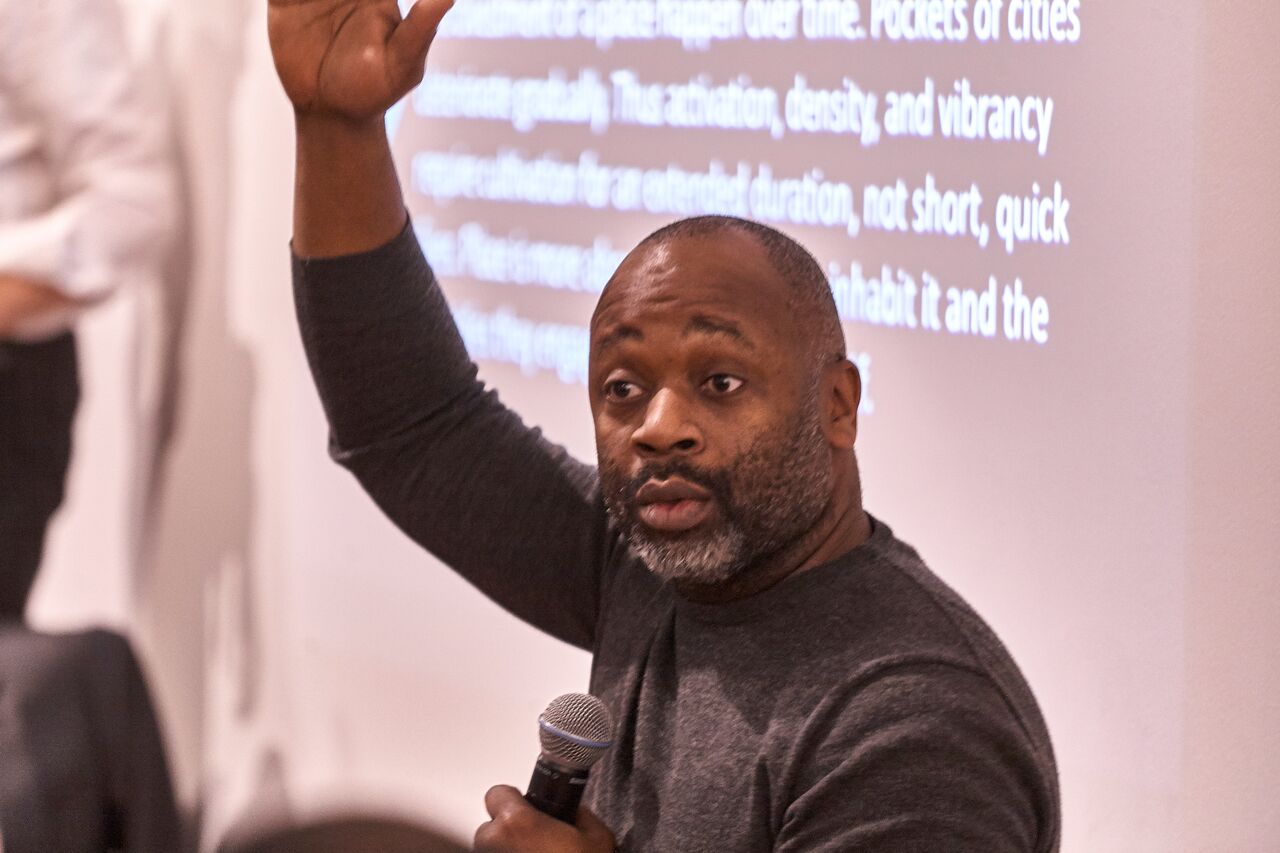

—Theaster Gates, Salon #9, Place Over Time

Crisis Times

I was very young, but remember well the explosive decade of the 1960s. In the early years, the outsized, hyper-real drama of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when missiles were aimed at our city and my home in a small suburb adjacent to the one-time “Arsenal of Democracy” and still-giant of US manufacturing, Detroit. The shocking, unforgettable scenes of violence that regularly flashed across the evening news of dogs and fire hoses trained on African Americans in the South. The indelible stain on my young mind of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham on September 15, 1963; the tears and stomach-churning grief that still come over me when I remember cutting out from the newspaper the photographs of the four girls, my age, whose bodies were blown out of the building after dynamite was planted there by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

The first March to Freedom organized by Dr. King was in Detroit in June 1963. At the time, the largest civil rights demonstration, the march to Cobo Hall drew 125,000 people, and it was there that he first spoke these words:

I have a dream this afternoon that my four little children… will not come up in the same young days that I came up within, but they will be judged on the basis of the content of their character, not the color of their skin.

I have a dream this afternoon that one day right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them and they will be able to get a job.

The March on Washington followed in August. By Thanksgiving, our beloved president and hero, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, had been assassinated. It felt like the world had ended. The decade was bookended by the murder of another beloved leader, the moral compass of the nation. The assassination of Dr. King—another cataclysmic tragedy that signaled the end of the world as we knew it—extinguished a great beacon of hope and ideals. Two months later, Bobby Kennedy was shot and killed. By then, Harlem, Watts, Newark, Detroit, and Chicago had already burned.

My soul, even in those early years, had already been hollowed out, a deep and porous space, by collective horror, grief, and rage in my own community. I was born in the wake of the Holocaust, and don’t remember a time when I did not know about Hitler and concentration camps and genocide: “extermination” was the word widely used to describe what was done to my people. Like many others, I learned early on what the world can hold for people denied their humanity because they are deemed to be different.

“The idealism of the 1960s, the bold, wild, confident exuberance, was also real. And the music... The exhilarating thrill, right there in the Motor City, of the Motown groove, the passionate crooning of black men and women, elegantly coutured, perfectly coiffed, who seemed, in my white-skinned Jewish world, to reach out and remind us of our shared humanity and capacity for love and joy.”

But we survived, and most Saturday or Sunday mornings of my childhood I sat in the richly adorned sanctuary of the Albert Kahn-designed Temple Beth El on Woodward Avenue—with its carved mahogany ark for the Torah scrolls, stained glass windows, and a suspended, sky-blue interior dome with frescos of Biblical scenes and the Statue of Liberty depicting immigration to the US—the most beautiful, ornate space I had ever experienced. I grew up in Oak Park, filled with eager, optimistic, determined descendants of Eastern European Jewish survivors, a small, protective enclave where we reveled in what we loved about ourselves and our culture: our manners and mannerisms, our speech and our food, for which we were despised and mocked by others. The kind of “loveliness” Natalie Moore talks about in black communities in The South Side. I learned that, however uncomfortable, it is okay to be different; important to stand up for the right to be different and be respected for those differences. I understood that one learns the rules, assimilates and infiltrates, shamelessly, without permission, because this is the promise of a democratic, pluralistic country, for the sole purpose of creating the portal that allows the waters of will, desire, and yearning to break free. That allows us to create the kind of society where we are obligated to see and value each others’ loveliness—whether we are comfortable with it or not; whether we like it or not.

The idealism of the 1960s, the bold, wild, confident exuberance, was also real. And the music. The songs of Peter, Paul & Mary, to which we sang along with our guitar-playing camp counselors, and cried—and later, of the Beatles, and Simon and Garfunkel—for the dreams, the promises of harmony and peace. The exhilarating thrill, right there in the Motor City, of the Motown groove, the passionate crooning of black men and women, elegantly coutured, perfectly coiffed, who seemed, in my white-skinned Jewish world, to reach out and remind us of our shared humanity and capacity for love and joy. There was the poetry of Bob Dylan and Stevie Wonder and Laura Nyro; cosmic tripping with Jimi Hendrix. And all the others, from the Stones to the Doors to the Jefferson Airplane, who proved we were capable of transcending the reigning social order to imagine and create—because we sure as hell were doing it in our consciousness—an entirely new reality.

But the idealism of the age evaporated along with the smoke from the burning times. In 1966, we danced and sang along, jubilant, triumphant, when Stevie Wonder belted out, “Baby, everything is alright, uptight, outtasight!” By 1974, Stevie’s tune, and ours, had changed:

… But we are sick and tired of hearing your song

Telling how you are gonna change right from wrong

'Cause if you really want to hear our views

You haven't done nothing…

Crisis Times Fifty Years On

We are living through a new cycle of extreme political and moral crisis. The surreal crisis is the grotesque reality of a reality TV POTUS; of an administration that is nothing if not a stage setting upon which are performed pantomimes designed to mask a moral vacuum; to mask the sucking sound of corruption and moral turpitude of such magnitude that it requires Herculean mobilization of all segments of our society—from the press to the clergy, civic organizations, educational institutions, business leaders, and individuals—to track, define, and attempt to maintain a vocabulary and visual protocol resembling civil order. This time, the supposed leader of the free world is in cahoots with the Evil Empire.

In the burgeoning domain that I think of as the Sixth Estate,[1] what we commonly, inadequately, refer as to the nonprofit sector—which some more aptly, if still inadequately, term the social impact sector—lies the potential for radical transformation over time. The task of this generation is to harness, using elevated levels of technology and, yes, of diplomacy, the hard-won lessons of the 1960s. We can no longer profess innocence or ignorance, or claim powerlessness, as all the information we need is available to us with the strokes of a keyboard. The revolution is being televised.

Photo by Brandon Fields

Detroit

Detroit was a revelation.

At the end of July, the Detroit Delegation, an adjunct group organized by Salon Member James Feagin, a consultant and real estate developer currently working with NEIdeas and Motor City Match, hosted a two-day program of events: small-group discussions, open to the public, around the Ethical Redevelopment Principles at The Baltimore Gallery with Founder Phil Simpson; a public performance and gathering at O.N.E. (Oakland North End) Mile Project ; a bus tour; a community panel discussion facilitated by Theaster at University of Detroit Mercy.

Delegation Member Cornetta Lane, Founder of Pedal to Porch, which sponsors neighborhood bike rides where area residents use their front porch as a stage to tell their story, was also instrumental in coordinating the events. So was Candice Fortman, Marketing and Engagement Manager at WDET, Detroit’s public radio station. Salon Member Bucky Willis, Founder of Bleeding Heart Design, Chase Cantrell, Founder of Building Community Value, winner of a 2017 Knight Cities Challenge grant, and Bryce Detroit, a cultural curator, member of the Oakland Avenue Artists Coalition, and Music and Culture Lead for the O.N.E. Mile Project, also hosted the events. The event was a first venture for the group, earnest, fledgling programming that contained within it the seeds of something profoundly transformational and powerful—for Detroit, and for neighborhoods and cities across the country that struggle against great odds, with limited financial resources, to build landscapes that reflect their communities, their history, and their aspirations.

Photo by Aaron Rose

On our way to the evening event, the group visited Submerge, a hidden jewel on 3000 East Grand Boulevard. Submerge operates as a wholesale music distributor; today their space is also a museum dedicated to Detroit techno. The group viewed electronic instruments and rare record pressings, as well as artwork and media, on a tour led by Cornelius Harris.

Photo by Aaron Rose

Afterwards, at O.N.E. Mile, we dined al fresco, adjacent to their structure, surrounded by prairie grasses and wildflowers. It was peaceful and quiet as we sat bathed in the amber rays of the setting sun. Beyond the hype, the ruin porn, the garish stadium with a cartoonish facade crashing the city center, this is Detroit, starting again. Land germinating. Buildings and streets reawakened, inhabited, tended. People getting on with their lives and gathering at the end of the day to talk. [Video: See an introduction by Bryce Detroit]

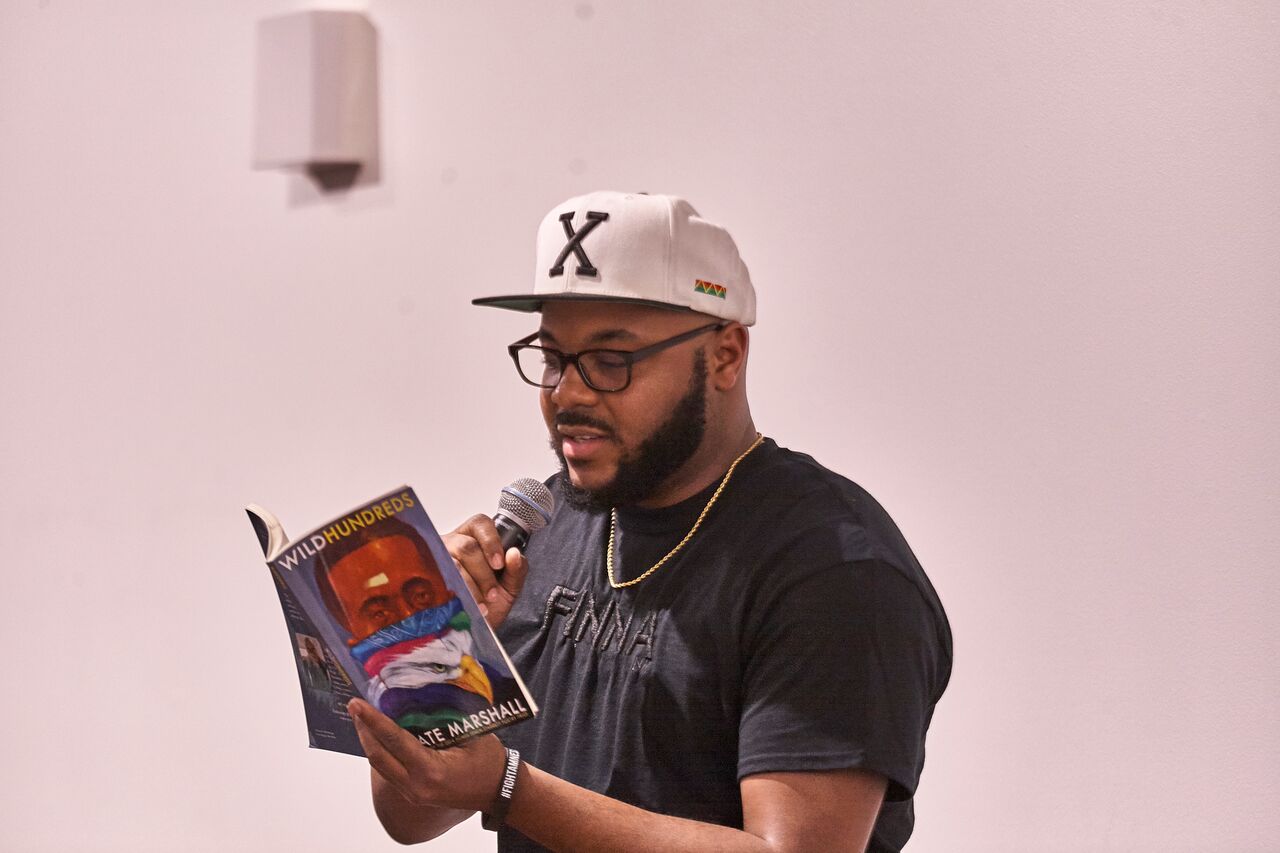

Photo by Aaron Rose

The O.N.E. Mile repurposed brick structure is open on one side to allow the space to act as a stage setting. We enjoyed a performance by Synergystic Mythologies: Bryce, drummer Efe Bes, and sonic cyberneticist Onyx Ashanti. The spoken word performance by Bryce that evening, when he asked “What is the root?,” was an exalted experience of listening to him speak in group sessions. A slim, wiry man with intense focus, Bryce often closes his eyes when he speaks, connecting, it seems, with an inner vision so vivid it does not allow for dispassionate distance or admit distractions. The large African beads I’ve seen him wear might be keeping him on the Earthly plane. [Video: Synergystic Mythologies performance]

Detroit is a majority, 83%, black city, Bryce is quick to say—and its revitalization is rooted in the ancestral traditions and wisdom that have sustained African peoples. As described in this piece from Model D:

Detroit, with its dystopic imagery of abandoned factories, fraught racial history, and 83 percent African-American population, has become a hub for afrofuturism. The city was the home of techno music and afrofuturist pioneers Drexciya and Carl Craig. Today, the philosophy is present in the programming and messaging of organizations like the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm… And numerous local artists, writers, and curators are harnessing the movement to create works that… have the power to heal and transform.

The bus tour the following day, in a colorful former school bus with windows open to the sights, sounds, and heat of a sunny July day, took us along Livernois Avenue—a few blocks from where I spent the first four years of my life—historically the Avenue of Fashion that is filling up again with specialty shops that also serve as community meeting places and cultural generators, like Good Cakes and Bakes and Detroit Fiber Works. Yvette Jenkins, who founded Love Travels. Imports., also on Livernois, hopped on the bus to guide us along the Avenue from West McNichols to Outer Drive, and to share her own courageous journey of building a business in Detroit from the ground up.

Photos by Aaron Rose

We passed the Fitzgerald neighborhood. Salon Member Lauren Hood is Co-Director of Live6 Alliance, a community development organization that focuses on neighborhoods, including Fitzgerald, that connect at Livernois and West McNichols, a.k.a 6 Mile Road. The American Society of Landscape Architects just honored Live6 Alliance with a 2017 ASLA Professional Award for the Fitzgerald Revitalization Project, a collaboration to create a greenway through the neighborhood on formerly vacant lots. On a visit to Delegation Member Darlene Alston’s A Little Bit Eclectic specialty tea shop on West McNichols, Darlene shared with us her commitment to mentoring area youth, and showed us the organic vegetable and herb garden she tends behind her shop.

Photo by Aaron Rose

Next stop was Salon Member Matt Naimi’s amalgam of recycling center, public art park, and community gathering place on Holden—a mural-decorated, monumental presence between Trumbull Avenue and the Lodge Freeway. At one time a warehouse for the grocery distribution business owned by Matt’s father, which Matt purchased as a family legacy and an investment in the city, the Green Living Science project reflects his untamed, uncompromising approach to community service: Matt refuses to allow cash to be exchanged at the site. He started Recycle Here! in 2005 when Detroit was the largest city in the US without a recycling program. The informal, grassroots effort became a fully-funded, city-wide program, and then this dyed-in-the-wool Detroit innovator launched the nonprofit Green Living Science to provide opportunities for young people to learn hands-on about recycling, with educational programs, field trips, and tours. GLS, now operated by Executive Director Rachel Klegon, a Delegation Member, has since grown to serve educators, workplaces, local communities, and other groups; and to initiate a grantmaking program for community-based projects. The Lincoln Street Art Park on the front lawn of the building is a sculpture garden featuring permanent and rotating art installations.

Unfortunately, the project may suffer from its own success and the success of the city in rebuilding its infrastructure, as new city regulations threaten some current operations at the site.

Afterwards, we drove to Southwest Detroit to meet with Erik Howard, a long-time youth advocate who founded and heads up The Alley Project. Erik still lives in the Carson and Pitt area where he grew up, and where he started Young Nation, which started TAP to harness the creative capital of young people in the community, especially “corner kids”—as opposed to “porch kids”—who, seeking familial connections and support systems they lack at home, experience rough initiations on the streets.

TAP brought together four constituents in the community: artists, neighbors, nonprofit organizations, and businesses. The group identified their common needs and assets, and gave young people opportunities to create street art on neighborhood garages as a canvas for their creative ambitions, and as a way to conceal—or confound—gang tagging. Today, TAP projects are among the many murals that pop out in Southwest Detroit as an expression of the area’s diversity and vitality.

People often ask if everybody around here loves art…No, this is a neighborhood, it’s not a compound. If we didn’t have people who were critical, we would not be creating an honest assessment of where we are at. If it wasn’t for people that hate the project, it would have a fence around it. They nixed it. The fence was our attempt to accommodate the most conservative neighbors. They got involved with the project and declined the fence. If you lock the fence, then it’s a challenge to get into it. If you leave it open, we can watch it all the time. The project is open.

—Erik Howard, The Alley Project, Michigan Municipal League Placemaking website

Photo by Aaron Rose

During our visit, Erik and one of the project architects, Tadd Heidgerken, from et al. collaborative (the Detroit Collaborative Design Center assisted with participatory planning and design in the initial phases) led us through the building they are redeveloping at the corner of Avis and Elsmere, which will serve as studio space for TAP, as well as a new business incubator. At one time, the building housed a shop that produced clothes designed for square dancing. Erik and his team are committed to establishing an enterprise that is equally respectful and representative of the surrounding community.

“Six days of violence and destruction destroyed whole swaths of the city’s commercial districts, and made plain the terrible cost of racial and economic injustice, and the police brutality required to enforce it. As one man termed it, the “high-income white noose” around the black inner city. ”

The Uprising, 1967

Surrounding this flowering of energy, ideas, and new configurations of brick and mortar, is the specter of Detroit’s history.

The Detroit Delegation events coincided—in a way that seemed divinely inspired—with events commemorating the 50-year anniversary of the 1967 uprising in Detroit. In the early morning hours of July 23, 1967, at the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount, Detroit police raided an unlicensed bar, or “blind pig,” that served African Americans barred from many whites-only clubs in the city, where people had gathered that night to celebrate the return of two Vietnam War veterans. A conflagration was sparked as people on the street witnessed 80 men and women being loaded into paddy wagons and taken to jail. Six days of violence and destruction destroyed whole swaths of the city’s commercial districts, and made plain the terrible cost of racial and economic injustice, and the police brutality required to enforce it. As one man termed it, the "high-income white noose" around the black inner city. George Romney, Governor of Michigan in 1967, and father of Mitt Romney, wrote these words during his tenure as Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, beliefs for which he was sidelined and later relieved of his Cabinet position.[2]

I would have traveled to Detroit for either of these events. The overlay felt like a miracle of dialogue and discovery not possible in 1967.

At an event hosted by Humanity in Action for visiting student interns at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Marsha “Music” Philpot, a self-described griot, and recipient of a Kresge Fellowship in the Literary Arts and a Knight Arts Challenge award, described a phenomenon for which my Detroit friends and I had no name. She talked about the “boomers who just love to hang out in Detroit.” The people who, as kids and teenagers, like many of my Jewish friends, were taken from their neighborhoods, their schools, and their friends—to some, seemingly inexplicably—to live in rapidly growing Northwest suburbs. I think of one friend in particular, who walked to the Jewish Community Center at Meyers and Curtis after school with her black and Jewish friends; took the Woodward Avenue bus to the DIA and the main library; and who, in 1968, moved to a suburban apartment complex, an island bordered by a highway and four-lane roads with no sidewalks. Philpot calls them “the kidnapped children.”

The Secret Society of Twisted Storytellers held an event at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, where, one after another, men and women told stories of unrelenting police surveillance, harassment, and beatings in the decades leading up to 1967. They talked about the Big Four—an unmarked squad car of plain-clothes officers who stopped people on the street wherever and whenever they chose. Two sisters who had been at the blind pig that night, barely out of their teens, told stories of their arrests and the days that followed. A man named Dwight “Skip” Stackhouse, a stage actor who met James Baldwin in 1979 while performing in The Amen Corner, and who later worked with Baldwin as an administrative assistant, spoke in deeply philosophical terms of the uprising, its lessons and legacy. A member of the Society, an African-American woman who staffed the registration table, later told me she had lived near 12th and Clairmount in 1967. Her father, a member of the Michigan National Guard, left the house each morning that week to patrol the neighborhood in a tank.

I had never heard these stories. The only stories I’d heard were the stories of people who, then or shortly thereafter, lived north of the now infamous 8 Mile Road—the dividing line between Detroit and the Northwest suburbs. Something the stories, or rather the storytellers I heard that week had in common was their acceptance of the fact of the uprising, and the devastating destruction, as a consequence of what came before it. I didn’t hear the anger and underlying disbelief I was used to hearing. The record store Philpot’s father owned was destroyed. He tried to resurrect the business in a different location, but couldn’t revive it, and he never recovered from the loss. Though Philpot and other people who told their stories grieved the loss of life, and of property and businesses—the commercial arteries and community gathering places of their neighborhoods—they didn’t assign blame, and they didn’t sound bitter.

Photo by Phil Brown

Detroit Delegation: The Evening Convening

The Salon Members who showed up for the Ethical Redevelopment series were courageous, inventive, determined warriors. Detroit warriors are tasked with an assignment that’s massive in scale, and their projects sometimes seem overshadowed by the enormity of the rebuilding required. But each achievement is of monumental value, especially the organic process of ground-up rebuilding, sending out those branches and roots that portend radical, lasting change.

The evening convening opened with an invocation by Bryce:

The conversation is a container in the 21st century of sacred space

Space intentionally created to hold the hearts, the love, the beauty

The trauma, the hurt, the healing, the celebration

Over and over and over again,

Let’s begin.

I am biased—not implicitly— about Detroit. When Detroit was in the house, Salon conversations got personal and intense, emotionally raw and edgy, very quickly. Detroit is like that.

“There are some discontinuities, [Theaster] noted, some bridges that need to be built between people who, through education and other experiences, have acquired a sense of agency, and those who have not… How do we restore agency, he asked, to those who have been stripped of it? The question is not whether we have the money or the capacity. The issue is relationships, not resources. How do black people talk to each other again? If we can’t talk to each other, he asked, how do we talk to white people?”

A woman asked a question about black space and agency. Where she works, she said, in poor black spaces, there is no sense of agency. Theaster talked about the systematic forces in this country that have historically stripped black people of their capacity to feel agency, whether by killing or shutting people up—the super smart people, by giving them jobs. There are some discontinuities, he noted, some bridges that need to be built between people who, through education and other experiences, have acquired a sense of agency, and those who have not. It got very personal when Theaster shared that he hasn’t told his cousins how he became successful. He hasn’t explained Ethical Redevelopment to them. In his own family there’s a disconnect between his knowledge and the knowledge of his sisters and cousins about how the world works. How do we restore agency, he asked, to those who have been stripped of it? The question is not whether we have the money or the capacity. The issue is relationships, not resources. How do black people talk to each other again? If we can’t talk to each other, he asked, how do we talk to white people?

Bryce picked up on the challenge of having conversations across a spectrum of personalities and identities, on the dynamics and opportunities at community gatherings, especially at black family reunions. An institution or ecosystem is a construct made of interconnected systems, he noted, designed to insert people to fulfill a function. We’ve learned to understand the world from a professional perspective. When we are at family reunions and community gatherings, it is okay to acknowledge the variety of personalities and identities entering the conversation in a different way, and to frame the conversation to each segment accordingly, because each of these people will fulfill their role, “the functioning thing,” in the ecosystem.

That said, when we talk about developing a community, Bryce continued, it’s important to name the social, political infrastructure in place that conditions folks out of their agency by introducing these very narrow box identities that align with a particular social order. People came up North through the migration to access a different point of industrial, economic identity. From being “a nigger, a slave, a sharecropper,” to being “a foreman, a lineman.”

““There is a gross assumption,” Bryce said, “that many of our people are just waiting for ‘the opportunity.’ The first opportunity people are waiting for is the opportunity to call themselves what they want to call themselves in love. See themselves as the divinely righted beings that they really are: creators, manifesters, co-designers, co-executors, perfecters of a reality they actually control.””

In order to bring people into conversation, to have people actively participate as agents of change, we must first provide programming that allows people "to get back in touch with their whole, healed, beautiful, loving points of self-identity." Let people have opportunities "to reflect, project, experiment with, and celebrate the most loving parts of themselves." It isn’t about money—money doesn’t do that. “There is a gross assumption,” Bryce said, “that many of our people are just waiting for ‘the opportunity.’ The first opportunity people are waiting for is the opportunity to call themselves what they want to call themselves in love. See themselves as the divinely righted beings that they really are: creators, manifesters, co-designers, co-executors, perfecters of a reality they actually control.” [Video excerpt from the panel discussion.]

Photo by Brandon Fields

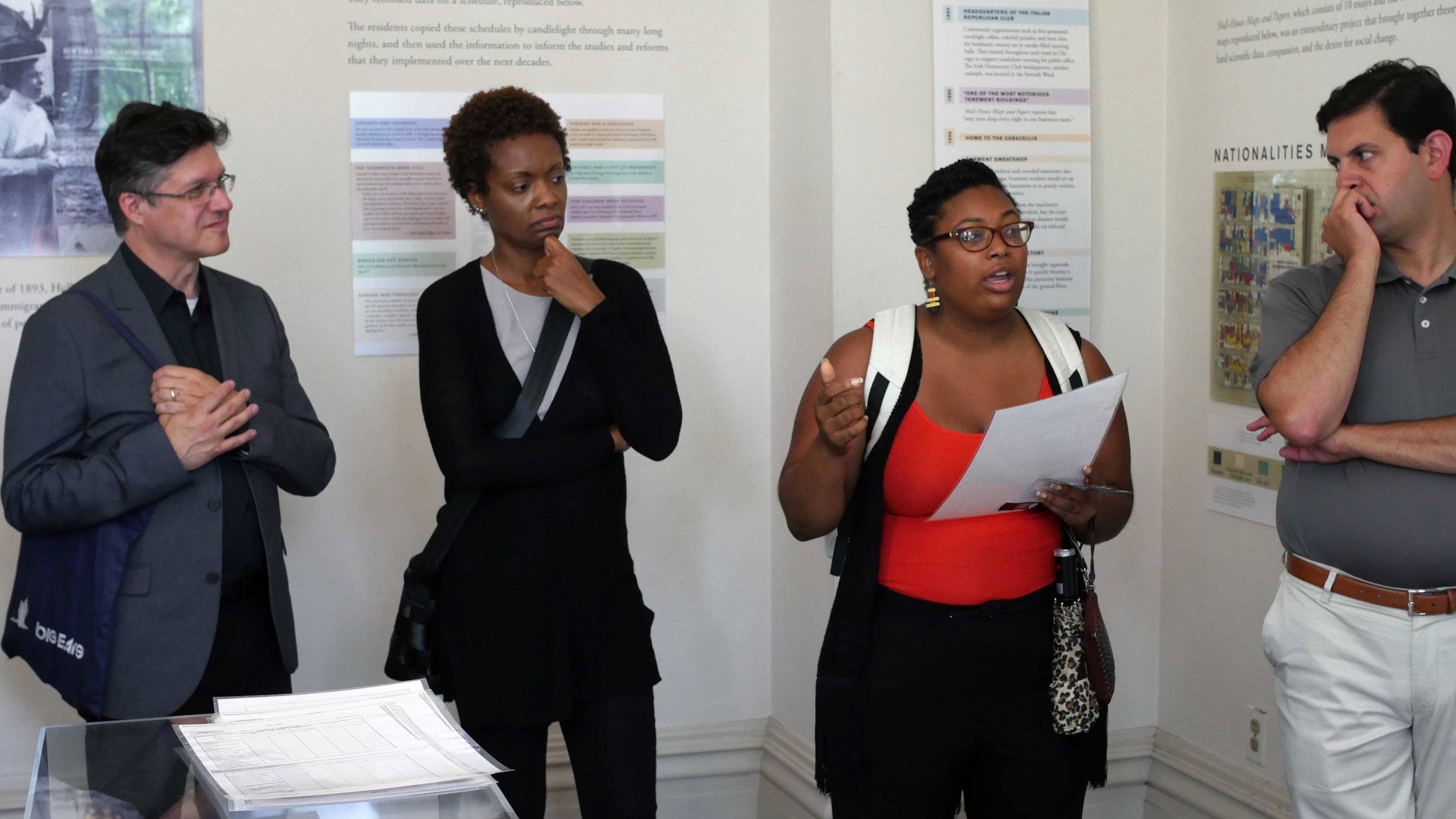

Salon Finale

Place Lab hosted a Salon Finale in June. The event brought together Salon Members, guests from Chicago, and the Detroit Delegation. An Impact Chorus—yours truly, Janet Li, Liaison with the Office of Resident Engagement at the Chicago Housing Authority, and Carol Zou, at the time, Project Manager and Artist-in-Residence for Trans.lation, an arts-and-cultural platform initiated by Rick Lowe and commissioned by the Nasher Sculpture Center—gave three individual readings at the beginning, middle, and end of the evening with reflections on the series. There were breakout sessions, a panel discussion, and a memorably delicious meal of catfish, greens, rice, and biscuits served in the Currency Exchange Café next door. There was much laughter as we ate and drank together in the open-air patio out back on that early summer evening.

The breakout session addressing “Your City as a Constellation: Assembling Effective Collaborations with Changemakers and Key Partners to Drive Scaled Impact in Ethical Redevelopment” was led by the Detroit Delegation. Melissa Lee, Senior Advisor for Commercial Revitalization at the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority, led the session “Building a Shared Community Narrative Through Historic Preservation & Placemaking,” and the session with Kevin Moran, Executive Director of Fairmount CDC in Philadelphia, addressed “From Paper to Pavement: Moving Beyond Planning to Implementation.”

A panel discussion, moderated by Gia Biagi, Principal of Urbanism and Civic Impact at Studio Gang Architects, crystallized into the kind of kick-ass conversation about Ethical Redevelopment—the opportunities and triumphs, and all the challenges that fly into your face when you pursue them—that you might expect with Isis Ferguson, Place Lab’s Associate Director of City and Community Strategy, Lauren Hood from Live6 Alliance, and Brent Wesley, Founder of Akron Honey.

Carol Zou closed the Salon Finale by invoking the figure of the subaltern.

I am haunted by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s landmark question, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” using a term coined by Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks to refer to one deprived of access to power—for Gramsci, the peasants and working class in 19th-century Italy. In my darkest hours of reflection the answer is “No”; in brighter moments the answer is, “Why the hell are we doing this work, if not for the most vulnerable in our society?” …In every participatory process we craft, we must remember that it is our moral responsibility to craft participation that centers people who are precluded from participation.

Photo by Brandon Fields

The Conversation is the Container

“Can you touch those who don’t know what it means to be touched?,” asked an elder from the community during Salon #2, when we addressed Engaged Participation.

“We are poor people and we are treated like first class slaves.” A man named Mark spoke during Salon #8, Constellations, a collaboration with the Chicago Torture Justice Center. Founded with a historic Reparations Ordinance in 2015, the Center fosters healing from police violence for the community and for individuals like Mark, who was tortured and imprisoned by officers under the command of Chicago Police Department Commander Jon Burge. Mark talked about returning, after decades in prison, to his home in Englewood, a neighborhood that had so deteriorated he no longer recognized it.

The fallacy, the grave mistake is thinking that the “subaltern,” the thousands of men and women like Mark in neglected, physically crumbling neighborhoods on Chicago’s South and West sides, throughout Detroit, and in other cities in the US, “waiting for the opportunity,” as Bryce said, are draining the resources of our society. This is a lie. Like the deluge of lies from the current head of the US government, they are meant to obfuscate the truth: that those who amass the most are most often the ones who only take, and who are draining the country’s resources.

In 1966, in an interview with Mike Wallace, Dr. King said “a riot is the language of the unheard.” While the figure of the subaltern still represents millions of victimized individuals whose voices are barely heard, they, we, are not powerless. Whatever we do, it will not take another 50 years to continue the conversation.

As we embark in a mindful, intentional way—surrounded by the evidence of history and stripped of illusions—upon the rebuilding of cities and communities, one corner, one relationship, one idea or building—or one hundred ideas for buildings, as Theaster exhorts us to do—at a time, we are armed with the power of knowing that what we do has never been done, not in these cities, not in our lifetimes. That’s change.

Aaron Rose, blog series author. Photo by Brandon Fields.

[1] The historic estates of the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners were followed by the fourth estate, the press. The alternative press became known as the fifth estate, some say based on the underground newspaper, “The Fifth Estate” published in Detroit beginning in 1965.

[2] Nikole Hannah-Jones, Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law. Propublica. June, 2015. An astonishing recounting of the fate of the 1968 Fair Housing Act.