On Wednesday, October 19th, Place Lab hosted the third Session of our year-long Ethical Redevelopment Salon. In this entry, Place Lab Operations + Administrative Manager, Naomi Miller, reports on the Session.

This Salon Session, we focused on Principle #3: Pedagogical Moments—opportunities for knowledge transfer that can happen at any stage of work and where the roles of teacher and student continuously shift. The Principle advises that when involved in mindful neighborhood-, community-, and city-building, we must practice a consciousness of these moments or anticipate how these moments can be structured as part of the development process. It is our social responsibility to bring people along for the ride.

PRELUDE

To show a nontraditional model of pedagogy, we visited Chicago’s Iron Street Farm, which is part of Growing Power’s urban agricultural community food system. Utilizing a 7-acre abandoned food hub, Erika Allen and her staff oversee year-round food production, vermicompost, mushroom production, an apiary, and urban pygmy goats. Salon members were given a tour by a staff member who once was a part of the organization’s program that trains and employs over 300 city youth annually, teaching them about these systems, methods, and production. By demonstrating and educating about equal access to healthy, high-quality, safe and affordable food, Growing Power’s achieves its mission to grow minds and to grow community.

Isis Ferguson, Place Lab’s Associate Director of City and Community Strategy, visited Growing Power prior to the Session; you can read about her visit here. Recently, Growing Power added a CTA bus to the Fresh Moves program, a mobile produce market that serves disinvested local neighborhoods.

The next site visit was to the University of Chicago’s Arts Incubator, operated by Arts + Public Life (APL) and the home of Place Lab’s offices. At the Incubator, the education department team asked us about an instructive moment or person in our lives, a question that elicited stories about family members, epiphanies, and time-delayed realizations.

APL staff members Marya Spont-Lemus, Quenna Barrett, and Gabe Moreno run a number of teen programs, including APL’s Design Apprenticeship Program, Teen Arts Council, and Community Actors Program, engaging teens in design/build, performance, and arts and culture administration, among other activities. These programs not only educate but employ teens, who learn essential job-related skills, leadership, and social development in addition to cultivating their creativity. A number of neighborhood teens have participated in the education offerings at APL, which have assumed a graduated structure to accommodate higher levels of engagement as the students master skills and look for more responsibility. The programs also maintain a level of flexibility to accommodate interests of the participants. For example, this past summer after redesigning and building new planters for our neighbor Chicago Youth Programs, the teens considered the play area and decided to build a new playhouse.

PART I

Over the course of Salon Session #3, many issues we’ve explored in the first two Sessions came up, including the intricate web of questions and ideas around community engagement and engaged participation. While it felt like we were at risk of repeating the conversations previously had, what emerged over the course of discussion were sincere efforts to talk about how complicated the issues are and dig deeper into them, unpacking and looking more closely.

To open this third Session, Place Lab screened a short highlights video from the first two that demonstrated pedagogical moments within the Salon.

Many of the issues raised in the previous Session were revisited throughout the night, such as the double standard that requires nonprofits to offer transparency and be mission-driven while traditional developers do not. Discussion also centered on the “triple tax” of doing neighborhood-based development projects—the extra costs associated with ethical and inclusive work. Ethical Redevelopment demands greater effort, which goes into listening, teaching, and working through layers of oppression in order to move projects forward. This triple tax often becomes a barrier to scaling up, while in traditional models of development efficiency is prioritized and projects become disconnected from the communities that are purportedly being represented.

“In Ethical Redevelopment, it is not for you to become a better colonizer.”

David Stovall, professor at the University of Illinois Chicago and high school teacher, took the mic and gave a stirring talk about pedagogy itself. Pedagogy is not just a theory of teaching, but also a method of inquiry on the very practice of teaching and the comparative value of instructional design models.

David gave an example from his own classroom. Speaking specifically of his high school students, David shared a question that he proposes to them: “What does a pedagogical practice look like using a racial justice frame?” The question is meant to get the students to address the underlying barriers to knowledge acquisition. In this instance, students are prompted to identify and examine structural racism, colonialism, isolationism, and marginalization. David acknowledged that he also gains valuable insight from the process, learning from his students even as he teaches. This is the heart of a pedagogical practice: it is liberating knowledge acquisition from the rigid model of instructor/student, compelling both sides to deepen inquiry and thereby strengthening the quality of understanding.

Through the pedagogical principle, David explained, redevelopers remain constantly aware that they are also part of the community they seek to serve, a driver and a beneficiary of the project. Instead of the singular question “How do I make my project work?,” the inquiry is multifaceted and the questions become: “Who has been excluded and under what terms? What is the redress for what has been taken? How do we reclaim agency?” From this deep, constant process of checking-in, a new framework emerges: “How do we make our project work?”

As David summarized it: “In Ethical Redevelopment, it is not for you to become a better colonizer.”

Following this academic discussion about pedagogy, Sam Darrigrand provided an example of direct application. Darrigrand, Workforce Development Manager at Rebuild Foundation, defined the program he manages as a business model with a community purpose: what can be learned while being on payroll? The program employs individuals who were formerly incarcerated and who are often deemed “unemployable.” Sam described meeting people where they’re at, finding opportunities for soft-skill development, and unpacking moments of conflict to see what’s behind them. The Workforce Development Program is being incorporated into a number of upcoming projects led by Theaster Gates, including Kenwood Gardens where participants will acquire skills in construction, landscaping, design, and related trades.

For the night’s final presentation, artist Carol Zou spoke about the project Trans.lation and her role as its project manager in the Vickery Meadows neighborhood of Dallas, Texas. Trans.lation began as a monthly series of pop-up markets by artist Rick Lowe and the Nasher Museum of Art in a mixed neighborhood of immigrants and refugees from 120 countries as well as American minorities. Today, the project is an arts and cultural platform used for resident-led councils, resident-taught workshops, professional development, and pop-up exhibitions, and asks “How do we build cross-cultural learning platforms in order to develop community capacity and leadership?”

The project employs art as a cross-culture translation mechanism, but over time it has, by necessity, had to evolve to meet the “ordinary” needs of its community. Carol shared some of these needs, such as how the offering of Arabic language class becomes far more complex when participants are facing barriers like inconvenient or broken transportation systems. Carol also expanded on how teaching often becomes an opportunity for learning in Trans.lation, such as when the organizers of a general American Sign Language class discovered from participants that their language-learning concerns were specifically tied to helping them study for their citizenship exams.

Carol emphasized the importance of language justice, and holding space for everyone’s preferred mode of communication. As Trans.lation has grown, Carol has had to realign expectations for the project's outcomes, and has established success measures that are neither sexy nor grand, but are authentically centered on the experiences and knowledge of the people in Trans.lation’s communities.

This idea of relinquishing power to a community and facilitating self-determination is a theme that reverberated through the night and in past Sessions.

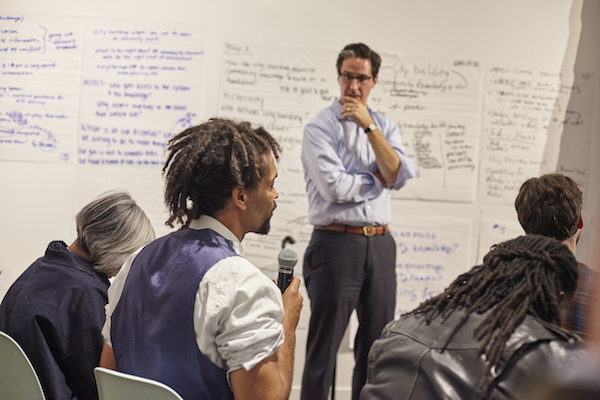

PARTS II + III

Following the presentations and panel discussion, members broke out into groups to discuss the following questions:

- What responsibilities do we have to the people and places in which we work?

- How can city-building prioritize community knowledge and build on its foundation?

- How do we recognize and interrogate our own skills or talents? How do we unlock our work so that teaching/learning can happen?

- Moments of learning and teaching can unfold in all aspects of work and across relationships. Give us an example of when you’ve seen the paradigm of education and knowledge-sharing enhanced, disrupted, or changed.

After a short break to mingle and refuel, the group reconvened. Most groups chose to discuss the second question, which resonated deeply with members. The discussion centered around assumptions, structural faults, and knowledge gaps that lie beneath the surface of determining a community, working with it, and making sure that its needs and opinions are heard and prioritized—or whether these concerns are even considered at all.

“Efficiency is inversely related to inclusion.”

Members pointed out that the structures created to engage a community often end up excluding them. For example, meetings are scheduled according to a 9–5 work schedule, but not everyone keeps those hours; this is particularly true in low-income areas where residents often work unpredictable shift jobs or multiple jobs.

“Community knowledge” was grappled with as an inherently complex term. Communities are not monolithic, and carry a diversity of experiences and opinions that require time to understand. Certain kinds of knowledge become prioritized over others, such as quantitative data that influences decisions and often disregards qualitative research. Salon members reiterated that traditional developers should take the time to recognize that the people in the community have a "Neighborhood PhD." The community development train moves quickly, and developers who disregard or fail to seek out what the community knows, risk undermining their own work. As it was phrased: “efficiency is inversely related to inclusion.”

A thought that emerged later on the topic of inclusion asked how both developers and community members can share in the benefits. As a member posed it: "How do I [a developer] become a target demographic and not just a fringe beneficiary?”

“Justice should never be determined by those who wrote a false history.”

Salon members also pointed out that when members of a neighborhood have found the time and the place to express their opinion, these members are often the most vocal individuals in the community and tend to monopolize conversation, leaving little to no room for the inclusion of other voices. It is also possible that these strong voices are not representative of the disinvested communities where so many of the members are doing work. As one member observed: "A grassroots organization could be a group of well-organized, rich white folks." Some members brought to discussion the fact that what we talk about at the Salon Sessions never makes it into “the room where it happens," and speculated what Ethical Redevelopment could really mean when the most impacted have no agency in the decision-making process.

“I wasn’t taught how to win at capitalism.”

One member reflected on the gaps in his own knowledge: “I wasn’t taught how to win at capitalism,” he said, and went on to explain that he had to learn a great deal about existing systems before he could even consider how to change them. It is not possible, the group agreed, to propose an alternative model to a system of which you are either unaware or do not understand. This ultimately raised an even tougher issue: that the “community” can become an obstacle to a project’s completion. Members suggested that this obstacle could be eased or overcome if developers took the time to ensure that knowledge flowed both ways.

PART IV

Salon Session 3 Takeaways

- Seek out and listen to black youth, as they are often not in the room.

- The engagement spectrum runs from efficiency to efficacy, depending on the factor of time.

- Be authentic in the way that you are, more so than the way you are doing.

- Teaching while working requires investments of time and patience.

- Learn both the history and the context of a place.

- Expose and examine the “bootstrap” cliché.

- Complicate expertise.

- Always think in layers.

- Be mindful of how inclusivity is utilized.

- Immutable policy prevents/is an obstacle to change.

- There is a triple tax in the extra work it takes to combat structural racism and oppression.

- Build coalitions together—look at past models, like Italian and Irish immigrants.

- Recognize the multiple sources of knowledge within a community.

- Ask yourself if community development efforts support people's right not only to self-determination, but to defining for themselves what that means and looks like.

PART V

After this rigorous discussion, Salon Members were invited to a performance staged in the foyer outside of the the Arts Bank's Johnson Publishing collection.

Three members of Honey Pot Performance—Abra, Joe De, and Meida (who is a Salon Member)—staged what they defined as a simulated rehearsal, an open showing of how they workshop ideas and movements. A long poem, read in alternating stanzas by each of the three performers, morphed into movement exercises that prompted Salon Members to call out a relationship between Meida and Abra. As Media and Abra entwined and broke apart, embracing and letting go, Joe De deejayed a cycle of evocative music ranging from jazz to R&B to blues.

Honey Pot Performance draws on ethnography, sociology, and fieldwork data to feed experimentation with methodologies of moving through space and exploring relationships. Honey Pot participated in the 2015 Crossing Boundaries residency at Arts + Public Life, and describes itself as “an Afro-diasporic creative collaborative community centered on feminist and fringe sensibilities.”

After applause and appreciation for the performance, Salon Members socialized freely in the Arts Bank, extending thoughts from the evening and sharing their own experiences. As one member gleefully called out, "Let's keep exchanging knowledge, people!"