Photo by Brandon Fields

Ethical Redevelopment Salon Series

Session 6: 01.19.17

By Aaron Rose

place over time

concepts: flexibility, nimbleness

A sense of place cannot be developed overnight… To be an anchoring space in a city, people have to be willing to spend time there. Hot, hip spots come and go. Trendy locations fall short of connecting “need” with “space.” Need changes over time and, as a result, space has to change over time.

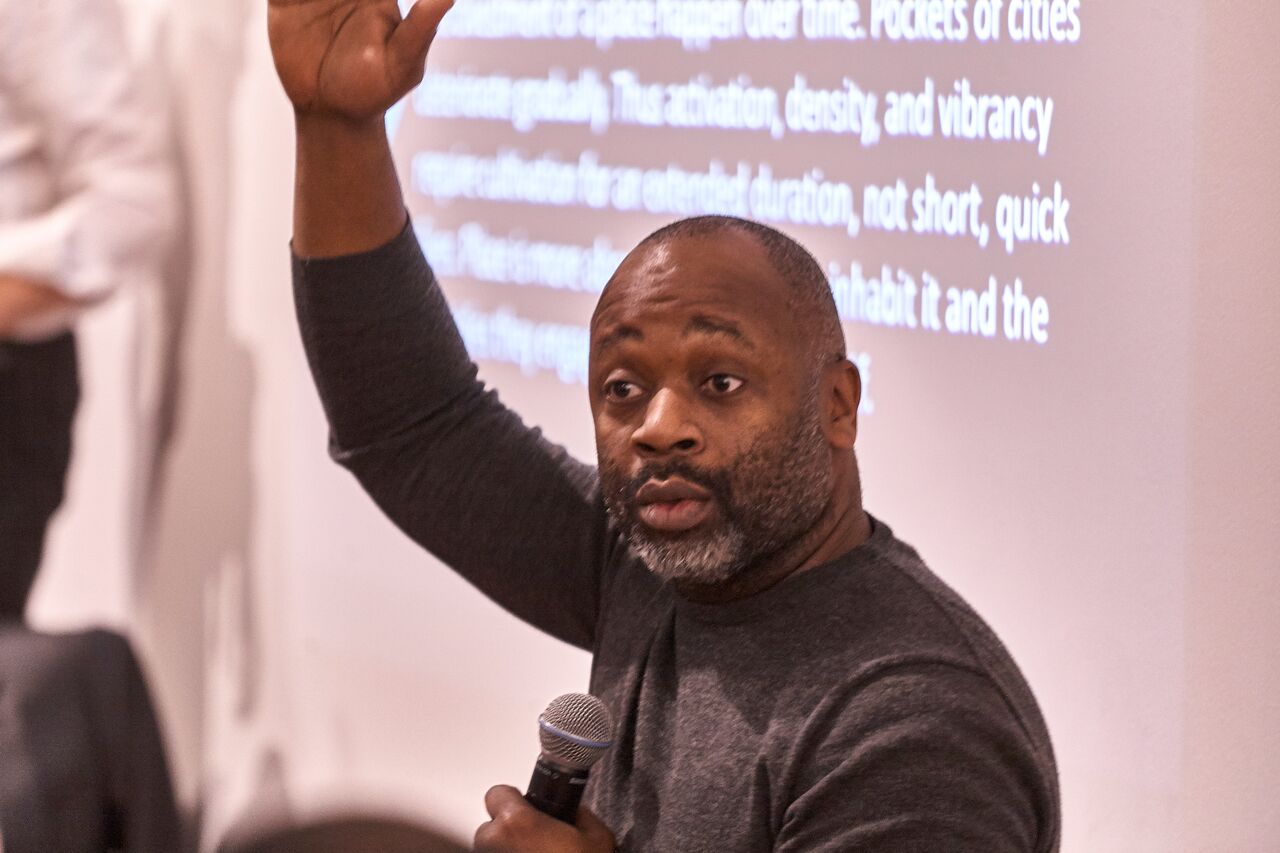

We gathered in the 3rd-floor gallery space in the Arts Bank for the evening Salon Session and the room was packed. It was an especially big group. James Feagin from Detroit, “The Emperor,” as I came to think of him, secured funds from the Knight Foundation to start a similar Salon series in Detroit, and the new group of twenty place-making practitioners joined us for our exploration of Place Over Time.

As I’ve written in earlier blogs, the Salon series coincided with the arc of the election drama. The Session on January 19 coincided with a day many of us had been dreading, and there was an elevated sense of urgency in our discussions. Emcee Steve Edwards was starting us off, when Theaster came running, breathless, into the room to launch the discussion, before he had to leave again. We were told it was a day of meetings with funders—a reminder of what it takes to sustain this work.

Theaster started by laying out what felt like a deepening groundwork for our discussion that evening, and for the work that lay ahead. And beyond his actual words, what I heard was that it’s time to get to the core of what we are doing in our Ethical Redevelopment convocations; to talk about what we really need to do to ensure that the redevelopment of communities we live in and care about is ethical.

He talked about his own history of moving into the Greater Grand Crossing neighborhood just ten years ago, to what he called “6918,” the one-story building he’d purchased on South Dorchester Avenue, despite concerns of family members for his safety. It’s difficult now for people to understand, he shared, when they see Stony Island Arts Bank, Arts + Public Life, the Arts Block, and now Place Lab, that this is how he started out.

Looking forward five years, the Obama Center will be open, and there will be intense interest in surrounding land, including land adjacent to the Arts Bank, which big architecture firms have started looking at. In another decade, this place will look very different. The lesson of the first chapter of his tale is that an individual can make change, profound change, in a neighborhood. Things can be rough—and you just need to work harder.

The second chapter of this story is about cities changing. One of two things will happen: you either participate in the change, or the change will happen to you. At the moment, we seem to have only one word for this change—gentrification. But there are other, more nuanced dynamics that are possible in pursuit of and in the midst of change. People have moved into or closer to Greater Grand Crossing because of Theaster’s projects, but has he caused or does this signal gentrification? Theaster cautioned that there are many ways people can make neighborhoods better. We need to know—to discover from and with our friends and networks—how we can support each other, even if the changes in our neighborhoods are looming 20 years in the future.

Lastly, how do we understand and address structural racism? What happens when people in a place wait on and are affected by structures? What does it mean when a government entity allocates resources in some places, and not in others? And what does it mean to create other structures, independently, to affect the course of change over time? For Theaster, the Arts Bank was an early example of what would happen if the black community had a super cultural institution. What would the building look like? And the visitors and activities—what would they look like? Sometimes, he noted, you have to “make the one thing in advance of the 100 things, with the belief that something can happen.”

Photo by Brandon Fields

There are people, Theaster continued, with power, authority, and connections. They see opportunity, and acquire objects and wealth through investments. On the other side, there are people who have been in a place, and who have the networks. What does this side, the side with the history, networks, and commitment need in order to be ready for the other side? To be ready so that there is equity when it comes time for conversation? In planning meetings, it’s a battle between the two sides. This side, the community side, needs to develop the same relationships, and collect the same kinds of information the other side has, that we haven’t had, so when it’s time to negotiate there won’t be a takeover. Theaster used the force of his hands coming together to illustrate what can happen when the force with power and authority is met with an equal force of power and commitment. One side doesn’t have to look like the other side, but it has to have “strong timbers.” It has to be a network of deep structure, including real estate lawyers and finance people, business people. That’s when the equity comes. It’s in the grappling and negotiations that the new jobs, new ownership, and new structures come. That’s when charitable organizations that complement for-profit entities get involved and provide advocacy that allows for a more complicated, integrated, malleable, messy mix—like a neighborhood—that works to the advantage of the community.

“The second chapter of this story is about cities changing. One of two things will happen: you either participate in the change, or the change will happen to you. At the moment, we seem to have only one word for this change—gentrification. But there are other, more nuanced dynamics that are possible in pursuit of and in the midst of change... Theaster cautioned that there are many ways people can make neighborhoods better. We need to know—to discover from and with our friends and networks—how we can support each other, even if the changes in our neighborhoods are looming 20 years in the future.”

Theaster ended his story by responding to a question from Richard Steele, one of the Guest Experts that evening, about persevering through a long cycle of place over time. We need to tell our children and grandchildren that they have to be good at math, to study hard, he said, because they’re going to be the ones to build on that piece of vacant land.

He talked about the vision, commitment, and relationships required to build places that do not yet exist, places of the future for our children. What do we owe and want to pass on to our children? Commitment to our communities requires a particular kind of belief—in addition to and beyond the cash of speculators. When the Obama Center is awake, there’s going to be a fight for our buildings. We, the community, will need to work through intimate relationships we develop between community members and individuals with power. We need to secure investment in individuals through CDFIs (community development finance institutions), and not wait for corporate investment. We need to create those connections and commitment between people who have money, power, and influence and folks who need to get stuff done.

A member of the Detroit contingent posed a question. Detroit, he said, has been developed for the past 50 years to shut out the city’s 83% black majority, who, in the decades since the auto industry in Detroit and people’s identities have been displaced and dislocated, have been seen as resourceless and valueless. Given the racialist media narrative to influence public opinion in order to affect public policy, can we construct new narratives so we see ourselves differently from the way we’ve been socialized to see ourselves? A group crafted a community benefits agreement (CBA), and the response was that the people who formulated the agreement lacked information—and even intelligence and creativity—required to propose something like this. “Listen to the experts,” they were told. Narrative affects who is given resources and allowed access.

Narrative can also fight stigma, Theaster responded. The hits don’t have to be huge. Black people can fight back with little hits. The Shinola narrative, for example, is very strong, even though I don’t know how many jobs they actually create: a few or a few hundred.

Photo by Brandon Fields

So what are our priorities?

It’s really on us. If you, as a black person, invest your money in conventional ways, you are helping gentrify a neighborhood in this country; you’re helping a corporation buy your grandmama’s house. We have to think more about these kinds of structural things: knowledge dissemination. Money aggregating by and for black communities. “And those things feel spiritual to me.” Your grandchildren should benefit from investments you made 30 years ago. There is something very palpable about place. I have a broad belief in black space, Theaster said, a transferable belief about black space. It doesn’t matter if it’s the West Side or the South Side. Whatever we call what we’re doing, it’s an attempt to demonstrate that we have the capacity to self organize. All of the solutions to the challenges we face are in this room.

Theaster left us with this question. Just like in school, when we’re asked to put that word we’ve learned to spell into a sentence, “what is the practice, the practical?”

Photo by Brandon Fields

Poetic Interlude

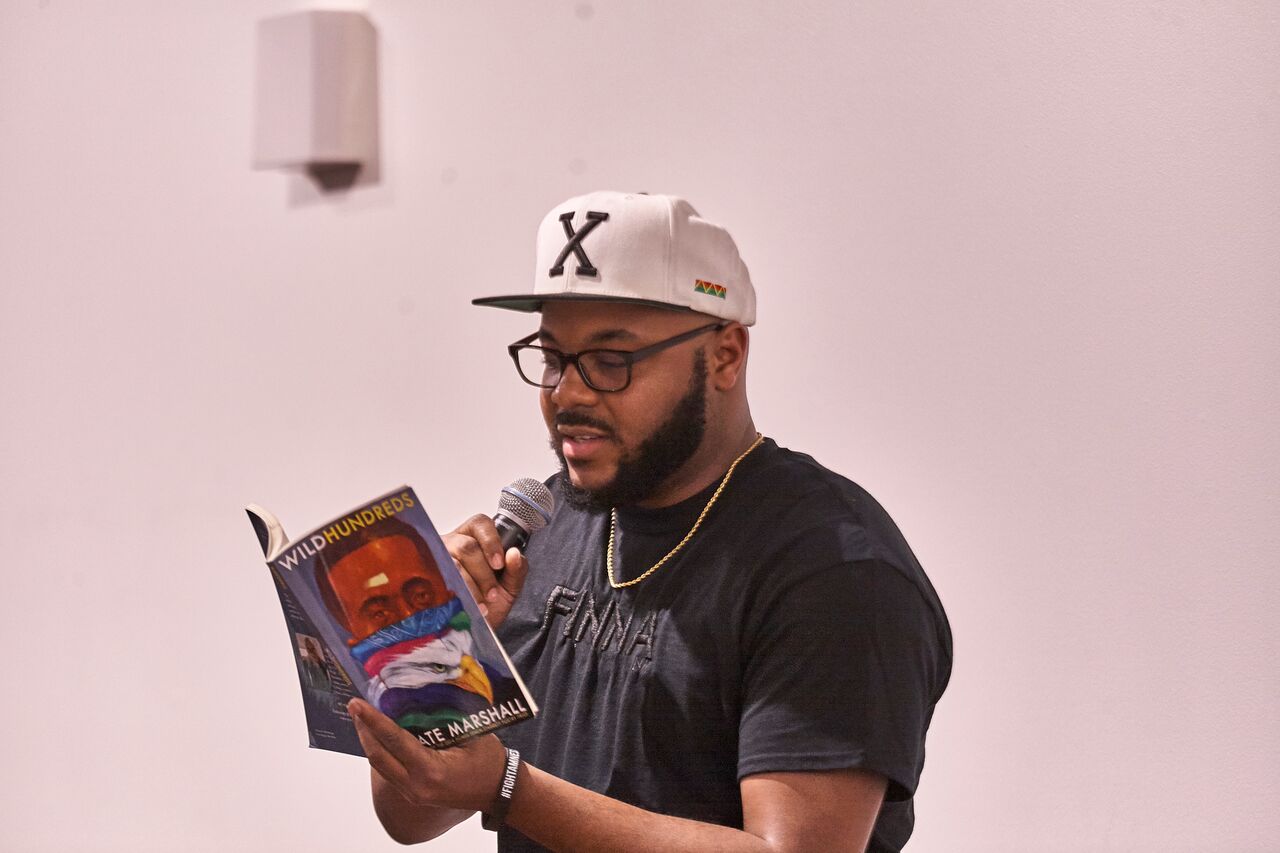

Following an introduction by Isis Ferguson, Place Lab’s Associate Director of City and Community Strategy, Nate Marshall presented a poetic interlude in keeping with “meditating deeply on cities.” Nate, Director of National Programs at Louder Than a Bomb, the world’s largest youth poetry slam, read two poems—elegant, naked and fierce in their beauty—from his award winning collection, Wild Hundreds, about a neighborhood on Chicago’s far South Side between 100th and 130th streets.

Salon

The Session featured conversation with two highly regarded Chicago journalists, both known for their integrity and informed perspective on race and place. Introduced by Steve as a “creator of communities,” Richard Steele is an elder statesman-like figure in Chicago. Richard joined WBEZ-FM in 1987, where he worked for 27 years and hosted numerous shows, including "Talk of the City," "The Richard Steele Show," and more recently, “The Barber Shop” show, broadcast on location at Carter’s Barbershop in the North Lawndale neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side. Richard was also a frequent contributor to other WBEZ-FM programs over the years, including "Morning Shift," "Afternoon Shift," "Worldview," "Morning Edition," "All Things Considered," and "Eight Forty-Eight." Richard has lived in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, located just south and east of Stony Island Arts Bank, for more than 40 years.

Ethan Michaeli’s recently published The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America is a beautifully written, 500-page tome—well worth the read—about the legendary weekly, The Chicago Defender. Ethan was a copy editor and journalist for the paper from 1991 to 1996. Ethan also organized and for 19 years led The Residents’ Journal, a publication by and for residents of Chicago Housing Authority public housing, which covers their communities, as well as Chicago politics and culture.

Ethan gave a fascinating account of the inception of The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott. Through the Haitian Pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Frederick Douglass, former US ambassador to Haiti, cultivated relationships among a generation of rising-star African-American intellectuals and community leaders. In addition to Abbott, they included writers Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Weldon Johnson (“Young man—Young man—Your arm's too short to box with God”); journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells; journalist, lawyer and Wells’s future husband, Ferdinand Barnett; and Oscar de Priest, the first African-American congressman from the North. The Chicago Defender was founded in the spirit of that gathering as part of an early-20th-century civil rights movement to “defend” against increasing oppression in the South, which wanted to roll back civil rights African Americans had won during the Civil War.

The weekly became the leading mouthpiece for African Americans, and shaped the course of history by encouraging black Americans to leave the South, prompting the Great Migration to urban centers like Chicago and Detroit. Initially, Chicago political leaders welcomed black Americans to this highly politicized city, but whites resisted and, in 1919 there were vicious race riots against the integration of African Americans. The Chicago Defender worked to break down the wall of custom and law that kept Chicago a segregated city. As the respected journalist Vernon Jarrett noted, in a circumstance where African Americans were ignored, their accomplishments and quotidian events of their lives were ignored, The Chicago Defender created the intellectual space for African Americans to celebrate each other. The weekly also reflected the sense of place in South Side Chicago that was an animating force in American life.

Photo by Brandon Fields

Richard talked about his experience growing up in Chicago. His family followed a typical aspirational trajectory, starting out at 32nd and Calumet in the Grand Boulevard neighborhood, in a basement apartment without a private bathroom. His parents, both of whom worked, put in an application for an apartment in the new Lake Meadows building, but their application was denied. It became clear the building was constructed, not to enhance living conditions for people in the surrounding community, but to attract more affluent people from other communities. His parents saved to buy a house at 73rd and Indiana. More than 60 years later, his brother still lives in the neighborhood, despite its decline over decades of black flight. Richard talked about communities of stable homeowners who formed strong bonds and block clubs, which change when original owners die. Their children either sell the house, or don’t want to live in it and instead rent it out to people who haven’t formed those bonds. This is how communities lose continuity of culture and purpose.

Richard and his wife have lived in South Shore for 40 years. South Shore is a great location, situated by the lakefront along South Shore Drive. But like other historically black neighborhoods in Chicago, South Shore has suffered loss of population and investment in recent decades that have lead to deteriorating conditions and an increase in crime, a familiar dynamic that the group took time to explore.

Photo by Brandon Fields

A young woman from Detroit shared that when she was growing up, she was told to go to school, go to college, and get out of the neighborhood. She felt attached to the place where she grew up and to the people who lived there, but she wasn’t told to bring her knowledge back and make the neighborhood a better place; she was told it was a place to evacuate. Someone else said it’s easy to take for granted that these old neighborhoods, the neighborhoods of our grandparents, will always be there. Sometimes these communities will maintain some of their original character, but become like a museum and lose their essence.

There was discussion about harnessing the power of personal relationships and networks that Theaster described earlier that evening. Richard sited the example of annual barbecues and picnics where former neighbors come together though they’ve been away from their original neighborhoods for years, sometimes decades. Ethan talked about the strong bonds of community among former residents of CHA projects like Cabrini Green and Robert Taylor Homes—how they maintain contact through Facebook and the kinds of events Richard described. Ethan also talked about people and forces in Chicago who wanted the CHA projects torn down, and who were consciously, actively working to destroy what some people considered “toxic,” “enemy” communities, and the power that exists in these communities.

The conversation came full circle to recognizing the power in black communities, across place and time. Building new systems and structures of black community will aggregate the knowledge and capacity required to take on historical structures designed to overtake them.

Monica Chadha, Civic Projects LLC

Livernois Avenue in Detroit, a street once lined with small, exclusive boutique shops between the elegant Outer Drive and upscale Palmer Woods enclave, had earned the moniker “The Avenue of Fashion.” Over time, the area declined and the businesses that had given the Avenue its reputation and its name were gone. To revitalize the Avenue, Urban Land Institute provided a long-range plan for the area, but the surrounding community sought to move forward to activate current resources and opportunities. Monica was invited by Dan Pitera, Executive Director of University of Detroit Mercy’s Detroit Collaborative Design Center, to create what became Impact Detroit, bringing together a collective, including economic developers and people with real estate experience, to develop a growth network. Using “a light touch” to take initial small steps, Impact Detroit worked in partnership with University of Detroit Mercy and small, local organizations who addressed immediate needs, such as coordinating a neighborhood clean-up, and conducting neighbor surveys. The group worked with Challenge Detroit fellows to develop a community storefront on Livernois Avenue, a pop-up that attracted hundreds of people to the area. Immediately following the success of the pop-up, the Detroit Economic Growth Council offered entrepreneurs, artists, and designers an opportunity to animate space rent-free for three months. After piloting their storefronts, four of the storefronts became permanent businesses on the block; an additional six businesses are expected to open in the near future.

Monica, as she describes it, went to Detroit “to incubate,” then started a parallel project in the Englewood community on the South Side of Chicago. There are shrinking cities; Chicago has shrinking neighborhoods. Monica began working with a CDC (community development corporation) in Englewood to animate big ideas for The Annex, an area adjacent to the Art Deco-style US Bank building near 63rd and Halsted. Historically, the area was the second-highest grossing commercial district in the city, after downtown Chicago’s State Street. Looming on the horizon was Whole Foods, which was planning to open a store in Englewood.

Again, starting with small steps, Monica and the team worked within a space they were offered in the US Bank building to bring in small-scale entrepreneurs who hadn’t had opportunities for growth; who needed a place to learn from each other, sharing knowledge and opportunities, as well as a place to work. Collaborating with some of Monica’s students from Illinois Institute of Technology and with Shed Studio, they developed the Englewood Accelerator space, which included classroom and training areas. The Accelerator has approximately 100 members who use the space, and has had thousands of visitors. Their intention wasn’t to create a plan for the neighborhood, but to look at a framework. They looked at game boards, and their impact, as a model, a thinking tool. They also researched vacant lots, including an abandoned rail line, which might become future nodes.

One of the Accelerator trainees, whose speciality is baked goods, has been picked up by Whole Foods and Starbucks. The Accelerator is now working with the former trainee on a production and café space in the neighborhood. Approximately 30 vendors from Englewood, including people from The Accelerator, have products now carried by Whole Foods.

Las Marthas

The evening before the Salon Session, Rebuild Foundation hosted a Moving Images, Making Cities screening of Crisina Ibarra’s 2014 film, Las Marthas. The film explores one of the world’s largest celebrations of George Washington’s birthday. The 116-year-old tradition in Laredo, Texas has evolved into a month-long series of historic reenactments and bicultural celebrations, many involving Laredo’s Mexican sister city, Nuevo Laredo. The most celebrated event is the invitation-only Colonial Ball hosted by the elite Society of Martha Washington, and the film focuses on the experiences of two young debutantes who make their debut at the Ball. One is the daughter of an established Laredo family, the 13th young woman in her family to debut at the Ball. The other is the daughter of a Mexican family whose newly acquired wealth buys her access to the tradition. Each wears an individually designed, 18th-century-style gown, which can cost as much as $15–30,000.

The film is a fascinating depiction of the legacy of US appropriation of Mexican land, and the strategies employed by Mexican families over time to maintain their land and their status as landowners and prominent citizens, while maintaining ties to their home culture. The film also reveals the poignant response of the two very different young women to expectations that they serve as carriers of culture.

Salon attendees were invited to the film, and I was delighted to see the contingent from Detroit, my hometown, arrive, straight from Union Station. Following the film, we had the kind of open, friendly, bad-ass kind of conversation I know and love and expect from people from the D.

Sabrina Craig, Cinema Program Manager at Rebuild Foundation, led off the conversation talking about why they chose the film and thought it relevant to Place Over Time. The fascinating and ridiculous rituals depicted in the film illustrate ways a community, whose citizenship was constantly shifting, but whose vulnerability was a constant, created an origin story, as well as a sense of self and place over time, so insistent on its status as American.

One woman brought up the Jack and Jill tradition in the African-American community, which starts at the age of six, and separates out people, starting at a very young age, by class.

A man said he wondered what the rest of the town, who did not participate in the elite ritual, thought about the pageantry. Considering that this film is being shown to us, people who are actively developing community, he had a couple of questions. First: how did the rest of the community in Laredo feel about this active celebration of assimilationist identity? Regardless of how small the elite community may have been, they are representing and broadcasting this assimilationist identity. This happens in Detroit where, of the 600,000 black residents, there may be only a small percentage who represent assimilation, but their identity takes up the majority of the market share because that’s the one the dominant culture wants to promote. No matter that there are 600,000 black people in Detroit who view things a certain way. If there are 20,000 who hew to the dominant narrative, the dominant culture attaches to that.

The second question: the young women in the film talk very little about white people, or about George or Martha Washington—yet they were dressing up like white people, and emulating the colonizers. How many of us are thinking and talking about things that are culturally specific, yet are dressing like the colonizer, and behaving, in our work, in ways that are counter-intuitive or counter-productive to diasporic African identities?

Someone else noted the ritual as a strategy for survival when people realized they had to look the part of colonizers to keep their land. Now, as they pass and wave to the 600,000, it really is their heritage. A visual artist talked about how interested he was in the fabric and the tactile aspects of the ritual. “There’s a lot of heritage in those threads.”

A man talked about being from a neighborhood on Detroit’s East Side and being invited to an event at the exclusive Detroit Athletic Club—where he wondered things like, do you have fresh flowers on the table for every meal? What does it mean to provide this kind of exposure to people who can’t live it, someone who has to go back to the East Side of Detroit?

Someone who attended the Eliel Saarinen-designed Cranbrook School in an exclusive suburb of Northwest Detroit, a private school I also attended, described the people who are part of these elite societies. He learned, as I also did, coming from a relatively modest suburban community, how wealthy, powerful families have markers—their names, the way they dress and behave—that have history and meaning, that they manifest in order to identify and maintain their power.

A man wondered why all that attention is considered necessary for girls. What happens afterwards in their lives? Someone suggested this is about maintaining or getting girls into those upper-class circles, by having certain things on their resume and getting into certain schools.

The ritual around George and Martha Washington started as a strategy designed to ensure people would be able to hold onto their land, and be safe. In Detroit, people also made strategic decisions to ensure they would be able to hang onto some kind of resources and assets, some place to grow from. How many of our 100-year-old strategies have gone awry?, someone asked. Our ancestors had strategies to assimilate that made sense 100 years ago, yet people continue these behaviors without examining if they still serve. How deeply can we investigate that collectively?

Someone noted that, at some point, they stopped telling the story, and it just became about the dresses. One man talked about the women in his family all making cornbread a certain way, in small batches. Family members started questioning the process, and went back to the elder matriarch, who responded that they made the cornbread that way because they only owned one small pan.

A tradition can be born of trauma, someone said. People may be reluctant to tell the stories, because they’re traumatic. One man said he wants to hear stories about the 1950s and '60s, but it’s difficult to persuade his grandmother to talk about that time. By keeping the traditions without knowing the stories, it’s possible to create new traumas.

The conversation turned back to the “A” word, and efforts to assimilate. How many of us were the first to go to college, or have a corporate gig? There are similarities between the tactics the community in Laredo had to use, and what our ancestors did who integrated in order to acquire land. We’ve had to balance being strategic with being uncomfortable.

Before we broke for the evening, Sabrina pointed out the other ritual presented in the film: of the religious figure giving welcome to a symbolic group of refugees and immigrants. How can this more meaningful ritual be made relevant and useful in community placemaking?

Photo by Brandon Fields

National Public Housing Museum

The afternoon session was devoted to a presentation and discussion with staff of the National Public Housing Museum, an organizing that has emerged over the past decade through the efforts of former residents of public housing to establish a site for honoring the history and legacy of public housing in Chicago, for social reflection and public dialogue. We met at NPHM’s temporary offices at Archeworks, with Executive Director Dr. Lisa Yun Lee, Robert Smith, Associate Director, and Daniel Ronan, Manager of Public Engagement. Lisa and a team that included Place Lab’s Isis Ferguson were responsible for the transformation of the Jane Addams Hull House Museum that Salon Members visited during Salon #2.

The Museum will be housed in the one remaining building of the historic Jane Addams Homes on the Near West Side, named for the Nobel Prize-winning founder of the Hull House settlement in the late-19th century. The first federal government housing project in Chicago, Jane Addams Homes housed hundreds of families over six decades, from 1938 until they were closed in 2002. The Museum is, in part, representing a golden moment in public housing.

The conversation focused on a range of issues related to public housing, starting with the role of government in providing subsidies for housing. We don’t acknowledge, in this country, all the forms of public housing subsidies. For example, the cost of the Mortgage Interest Tax Deduction (MID) for homeowners is about 80 times the cost of investment in public housing. US government subsidies for suburban housing after World War II was the largest public investment in housing in the country’s history.

Public housing in Europe is part of a larger commitment to public education and universal health care. In the US, in the early-20th century, there were similar questions, in the context of a capitalist society, about the commitment of a democracy to the public good, and government’s responsibility for public welfare. As Lisa pointed out, in one short generation, we went from a definition of welfare as something that connoted well-being and good health to something that “lazy poor people need when they’re not trying hard enough in a capitalist society.” How did this happen?

The conversation turned to the insistent power of white supremacy. We talked about historical events that created backlash and caused the US to revoke a stated commitment to democratic ideals. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed to desegregate life in the South; to integrate public places like swimming pools, and ban separate public facilities, like drinking fountains and restrooms. But the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 called for desegregation in the North. Banning segregation in housing also meant banning segregation in schools, which had entirely different implications. White Northerners were less sanguine about desegregating their communities and schools than about desegregating swimming pools and drinking fountains in the South.

In the course of our conversations, Lisa recommended a few relevant articles—investigative journalism about housing policies and public housing in the US. One is Nikole Hannah-Jones’s piece for Propublica, "Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law."Jones’s piece is an astonishing recounting of the fate of the Fair Housing Act, which, to be honest, brought me to tears.

I am old enough to remember the Civil Rights Movement, the Johnson administration, and the 1967 uprising in Detroit. The article reveals efforts by George Romney, former Governor of Michigan and father of Mitt Romney, who was well regarded by Democrats like my parents, as well as Republicans, to desegregate public housing when he became Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the Nixon administration. His commitment to interrupting segregated housing patterns in the US, “which he described as a ‘high-income white noose’ around the black inner city,” caused him to be expelled from Nixon’s cabinet. When have we last heard this kind of discourse from an official in the federal government? What opportunities were lost, almost 50 years ago, when Romney was sidelined?

Investigative reporter Jamie Kelvan, who broke the Laquan McDonald case in Chicago, and who has been writing about public housing for 25 years, initiated a longitudinal study about former Cabrini Green residents. The study, which tracks every family who lived in Cabrini Green to find out where they went after leaving the housing project, is being conducted by the nonprofit organization he founded to do this work, Invisible Institute.

Lisa talked about exposing myths about public housing, and recommended the book Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy.

NPHM will use storytelling to distinguish between myth, perception, and reality. Their challenge is to demonstrate the effects of power and place. Through the power of objects and oral histories, NPHM will explore housing as a human right, and examine assumptions about public housing and public housing residents. The Museum’s main artifact is the building itself, which visitors will experience directly through a series of architectural encounters. They will experience the “poetic ruins” of the space, after 15 years of abandonment when it was left in 2002. NPHM will employ Hip Hop scholarship, meaning style as a form of resistance, to demonstrate how people who lived in Jane Addams Homes transformed the apartments, using paint, wallpaper, and other materials to make the spaces their own.

Exhibition space in two separate apartment spaces will interpret ideas and experiences of home through the stories of four generations of different families who lived in the building. Public housing residents will serve as museum educators.

NPHM storytelling will be informed by South Africa’s landmark Truth and Reconciliation Process. The process defined four different kinds of storytelling truth: Factual or Forensic truth; Personal or Narrative truth; Social or Dialogic truth, which brings together and makes sense of disparate narratives; and Healing or Restorative truth. The website Proving the Holocaust offers the best definitions I was able to locate online of the Four Truths.

Healing and Restorative truth, which integrates all the truths and seeks acknowledgement and healing through an ongoing process of restorative justice, is the most important truth, and is the real work of National Public Housing Museum.

Photo by Brandon Fields