Many cities, regardless of where they are located or the combination of factors contributing to their context, suffer the same challenges—disinvestment and neglect, population loss, abandoned buildings, and pockets of almost immutably bleak landscapes. Far too often, the "solutions" offered in the face of these issues is singular, an idea that exists in a vacuum.

No single building, individual, or program can reroute a neighborhood’s trajectory. Neighborhoods are successful when compound ideas exist with expanded relationships and networks of opportunity. In order to propel work forward, attract these variables by providing the community with a platform.

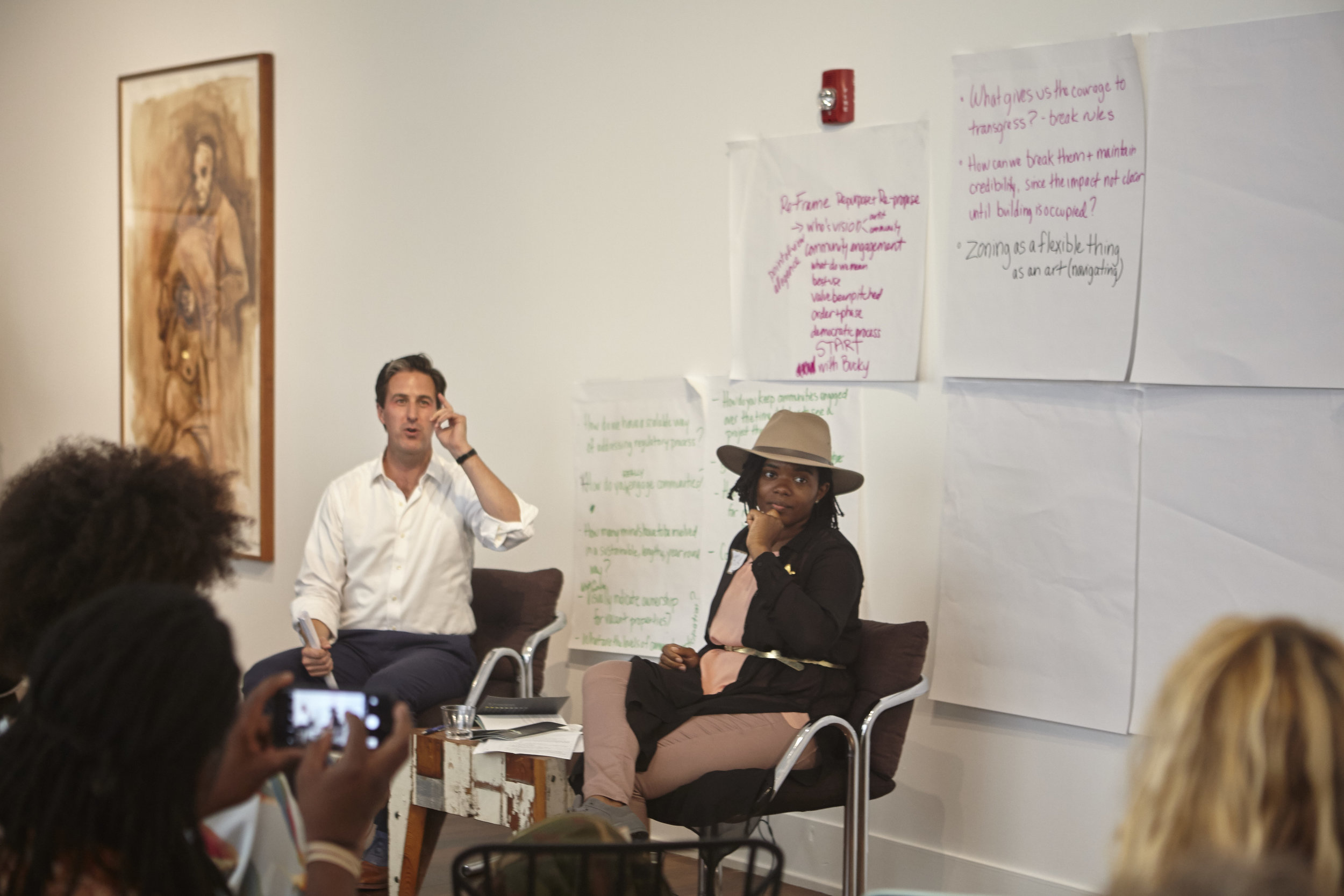

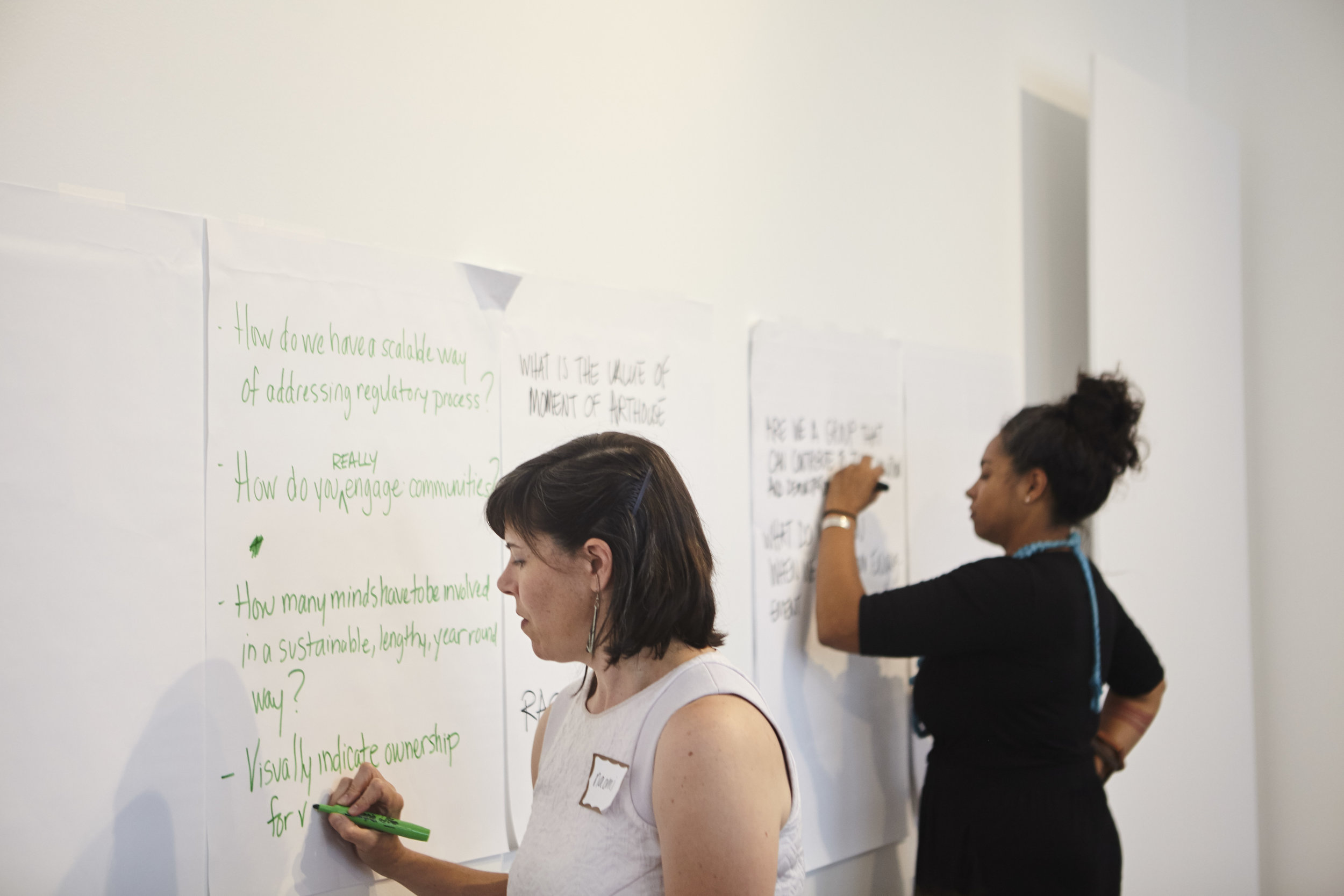

A platform serves as a foundation that creates new social possibilities, a real or symbolic structure that incubates new economic or artistic prospects. Platform-building means developing opportunities for people to gather and commune. These opportunities do not have to be flashy or expensive or excessively programmed. The event—what is happening—is beside the point. The point is that folks are meeting, exchanging, and learning.

Creating a platform is to create intentional hang time, which builds community through a space that encourages deep conversation, new friendships, and, ultimately, a community of people who want to be a part of transformative work in the neighborhood. A space where like-minded folk can come and say, “What else can be done? What can I do 10 blocks away from my block? How do I share what I love to do with others?”

Platforms in Action

Owned and operated by the indefatigable Eric Williams, The Silver Room n Hyde Park is a boutique retail store—and so, so much more:

“Located in the heart of Hyde Park, The Silver Room is much more than a storefront. The Silver Room is a gathering place, event space and artist gallery. The Silver Room represents community, culture and art.”

The Silver Room, in addition to its retail offerings, is renowned for its annual Block Party, its long-running open mic "Grown Folks Stories," its gallery offerings, yoga classes, and the opportunities it provides for young, local artists to create, learn, and network.

“[The Silver Room] is a hybrid of retail, event space, art gallery, community gathering place. A lot of it is locally made. It uses local fashion, local art. It’s a gathering space with a social impact to it. ”