On Thursday, November 17th, Place Lab hosted the fourth Session of our year-long Ethical Redevelopment Salon. In this entry, Place Lab Operations + Administrative Manager, Naomi Miller, reports on the Session.

This Salon Session, we focused on Principle #4: The Indeterminate—a guiding tenet built on concepts of imagination, intuition, and faith. The Principle encourages an approach to redevelopment work that permits for the suspension of knowing, embracing uncertainty, accepting ambiguity; believe in your project but resist believing there is only one path to achieve it.

PRELUDE

In response to the first three Salons, we heard from many members that they wanted more time with each other—more time for unstructured discussion and hanging out. The Indeterminate seemed like a perfect Principle for this to happen. In the early afternoon, members met at the Listening House on Dorchester Avenue for this undirected purpose. After a thorough tour and narrative arc of the Listening House and Archive House by Place Lab team member Mejay Gula, visiting guest expert, Leslie Koch, talked about the project she had shepherded from idea to implementation for a decade: the redevelopment of Governors Island, in New York, as a dynamic public space. It being a week after the Presidential election, Leslie played a video of the dedication ceremony this past summer, pausing to remark that everything she spoke about feels that much more important.

Formerly a military base in the New York Harbor, Governor’s Island is now a public park operated by the Trust for Governor’s Island and is largely programmed by the public. Salon Members listened as Leslie described how she and her team figured out the project as it evolved and navigated funders and government without a primary vision. Leslie detailed an open submission process for exhibitions, installations, and programs on the Island. Without a formal review process, or a budget, this approach meant people were truly allowed to dictate the type of activities and programs that took place throughout the year. This democratic/anarchic, approach felt like a stark difference between the highly curated and closely considered programming that might take place in other premier public spaces. The assembled group asked questions and shared thoughts as they drank tea and ate snacks. One question probed the importance of context and place in that the project had singular factors—an island in New York, a major city with enormous cultural capital—but could such a project succeed elsewhere?

PART I

A sedate Theaster Gates opened the Salon with some thoughts also influenced by the election. He called on members to think about the challenges and complications involved in their projects—how city structures and a lack of courage make things that much more difficult in forging a path for their work. Drawing parallels with the state of the country, Theaster offered that power can be gained from embracing this moment of indeterminacy, that “things that seem symbolically and realistically out of our control—there are still ways to affect change with the people we touch and the people around us.” With Steve Edwards, they agreed to turn towards the adversity, to meet it instead of turning inwards, and to more fully engage networks of people, one of which has been formed through the Salons and is proving to be greater than its grant-based intention.

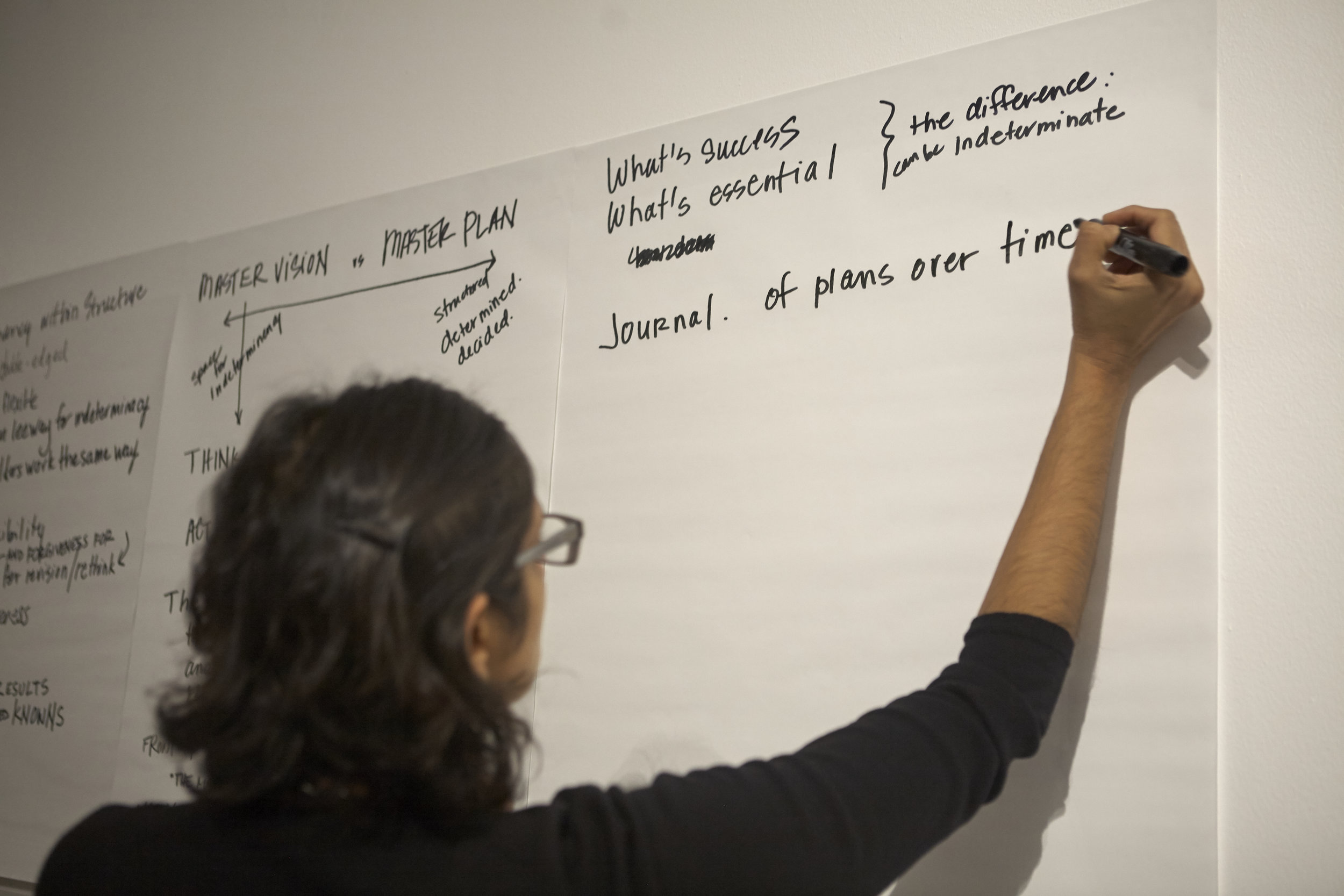

To flesh out Theaster’s introduction of indeterminacy and the topic for the evening, Steve compared the standard development process with that of Ethical Redevelopment—how the traditional process requires an endgame to satisfy risk-averse investors and to meet the litany of requirements for local and state governments. For Ethical Redevelopment, which prioritizes art and culture to lead interest in disinvested neighborhoods, The Indeterminate plays as much of a role in the process as a determined plan does. It’s an element familiar to artists as they turn an idea into substance—the unknown teaches and leads their practice so that a path is a process of discovery. Ethical Redevelopment leaves room for project iterations—a version, then another, then another—that are refined over time, leveraging serendipity and considering imagination and belief as assets.

“What question you ask is probably the most important thing you will do.”

With this initial definition in mind, Steve welcomed Leslie for a brief discussion about the initial phases of turning Governor’s Island into a public park that places arts and culture at its core. Leslie revealed that they had a Master Plan but no money in which to carry it out. Instead of clarifying a vision, she took the approach of recognizing that cities are inherently messy, drew a parallel with the artistic process, and went from there. “What question you ask is probably the most important thing you will do,” said Leslie. Her question was “What to do first?” rather than “What will Governor’s Island be?” In working with governments, the question you ask frames (and reveals) the situation even if you don’t know what it is. The language you use is also of utmost import—drop often esoteric field-specific terms and colloquialisms, instead using words and structures that are comprehensible across communities. Clear language allows for clearer, accessible projects. Learn what Governor’s Island has become based on this approach.

PART II

Three Salon Members briefly presented about their respective projects, each of which are at different stages and scales, and have different goals. Brent Wesley (aka Wesley of Wesley Bright & the Honeytones) recounted how he created the Akron Honey Company (“It was an accident, really”), and described being convinced by a friend to become a beekeeper and use Brent's newly acquired lot for making honey. Brent figured that not only would he never have to buy honey again, he would also be able fulfill his aim to add value and provide a community-use for the lot. Through a number of iterations, Brent grew the company to a place he never imagined: cosmetics. Along the way, he learned to make and sell microbatched honey, produced a Market Day on a quiet street, and was a contestant (winning and ultimately declining an investment offer) on Cleveland Hustles.

On the other end of the project spectrum was Angela Tillges, who spoke about recently relocating from Chicago to her hometown of St. Paul in order to implement (with one colleague) the Great River Passage (GRP) initiative for the city. The ambitious GRP master plan includes 321 arts-and-culture projects, which Angela is charged with seeing to fruition, in the parks, public space, and natural land along the city’s 17-mile stretch of the Mississippi River. Two months into the project at the time of her Salon presentation, Angela said she’d spent a few days in the office and the rest of the time onsite, observing and talking to people without revealing her job title. Hefting the sizable, weighty publication that is the GRP master plan above her head, Angela pointed out its determinacy while noting that the process of enacting its prescribed steps and number of projects is anything but. She thought of the projects as seeds: some will fail, others will become something else, some will bear fruit—and she will be an attentive gardener.

Somewhere in between the self-starting Akron Honey Company and a city-directed initiative lies the efforts of Keir Johnston and Ernel Martinez of AMBER Art & Design, an artists’ collective in Philadelphia. AMBER is working with the Fairmount Park Conservancy (FPC) to repurpose one of the park’s disused mansions in the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood and activate it as a museum that preserves the cultural identity of the neighborhood as it changes. Keir and Ernel described the history of the ethnic and cultural makeup of the neighborhood, which began as a WASP-y summer retreat, changed to a mixed-income community populated by Jewish people, then to a disinvested neighborhood almost exclusively populated by African Americans. Ernel and Keir said they are in the process of talking with the existing coalitions and networks in the community. By creating partnerships, securing the structure, and gaining the residents’ investment, they said they hoped to make an institution that they can hand to the residents for self-stewardship.

PART III + IV

During the discussion with the panel and the following conversation with Steve, Theaster, and Leslie, we mined the concepts that underlie The Indeterminate—imagination, intuition, and faith—finding links and new aspects. One of them was credibility. In order to create believers in your project, you need to build credibility. This can happen through people who already know you, which is how Brent received early support—through his family, friends, and neighbors. Leslie approached it from the opposite side: she was the government and needed win the trust of the tax-payers. She built credibility through being consistent in her messaging of what she was going to do and then actually doing what she said: transparency, narrative, and being clear and consistent. Theaster needed to build credibility early on with the city before they would fund him because he didn’t have a track record, a place many people find themselves at the beginning of their work. Sometimes meeting the interests of a city first builds the credibility, which allows for flexibility further down the line. Trust, faith, and belief are highly valued foundations of any neighborhood-based, multi-partnered project and a lot of work goes into establishing them.

Theaster discovered that methods of iteration work well for building credibility. He observed: “Indeterminacy is closely related to iteration.” An iterative process allows a version to follow another, changing each time in response to feedback on the previous one. But iterations are often superseded by the hype around master plans, which is determinacy defined. Much of the discussion volleyed back and forth between these two ideas, noting the nuances of each. For example, master plans are often best used for discussions with funders and government—people who feel reassured that some sort of map and end game exists. It’s another piece of the credibility puzzle. But master plans are often of little to no interest to the public; as Leslie noted, “Humans don’t relate to master plans.” They’re exhaustive, exhausting, and exist next to reality instead of in it. Some members pointed out that master plans have been used as tools to deny access for a project. Theaster commented that there might be a way for them to be turned into a tool that works for you—make it a document that actually communicates and connects instead of being an unrealistic explosion of imagination and excitement.

Our discussion exploring the tension between master plans and iterations also highlighted the tensions between the priorities of different groups of people involved in a project's process. Developers, funders, neighborhood members, and artists each have different relationships to risk, and can easily and often find themselves in opposition. While funders and investors work to lower the unknowns and manage fear, artists inherently embrace risk by taking leaps of faith in order to bring something new to light. Suggestions were made about how to work around these conflicts. Artists could work with their social and cultural capital (and what exists with neighborhoods and partners) before even broaching economics—they might be surprised how far this goes. Another approach underlined the usefulness of iteration for several groups: they can show investors that there are people who will use the space, and the neighborhood sees that the space is for them. In general, members agreed that it’s easier to begin at a low-cost basis, or as Leslie phrased it, “Think big, act small.”

Leslie also emphasized the importance of narrative, language, and framing. She encouraged members to use real language and to be honest with all individuals on the power spectrum. You need to be clear on what you are about and why you are different. Shaking her head, she described some of the language she used in her narrative early on because it acted more like filters and veiled messages rather than stating clearly what was going on. And it’s important to know when you’ve run ahead of your own narrative—assess when it needs to be revisited and revised. Theaster nodded in agreement that language can work against you later in the process: “Don’t box yourself in by using a certain kind of specificity when no one’s asking for it.” Leave space for change.

Space is also needed for inefficiency, a point Theaster made by saying “Iteration makes room for inefficiency.” He underlined that inefficiencies are a part of the process, and need to have a meaning and carry a value—if they are perceived as a waste, then people become fearful of iteration. What if the government valued The Indeterminate as much as any other box to check off in their process? Room for error, for iteration, for learning and living is needed. This musing lead to another one by a member who asked how we could include developers in these conversations, how to show them the pros and cons of ambiguity versus results. It’s assumed that only artists are skilled with working with the indefinite when city planners, programmers, and project implementers work very much in the same way.

Part V

Salon Session 4 Takeaways

- The role of curiosity—ask questions, listen, learn, pursue your interests

- Master planning works for funders and government, not as effective for residents

- Build room in a master plan for The Indeterminate

- Use iteration to begin at a low-cost basis, build credibility, allow for efficiencies, and minimize risk

- Be intentional and consistent with narrative, language, and framing

- Ask the right question for the project

- Use social and cultural capital for buy in

- Risk means different things to different people

- To build credibility, be honest, clear, and transparent

- Leave room for the project to evolve and be discovered

Part VI

At the close of these various threads of conversation, Steve invited members to talk to each other, tell each other stories about the work they do, and generally socialize. Again, we wanted to make sure the members had time to connect and have casual, intimate conversations. We also set up a Confessional Couch where members could tell a story about their project in front of a video camera. Videos will be made available at a later date on our website and Ethical Redevelopment group page on Facebook. Feel free to join the group and learn more about the projects our members are doing around the US and engage in discussion.